In this week’s newsletter, we get a glimpse into Performa founder RoseLee Goldberg’s media diet, head to Harlem to preview the new Studio Museum, and more.

Good morning!

Olivia here. This past week, I spent some time reflecting on a recent New York Times Popcast interview with one of my favorite pop stars, Rosalía, whose fourth studio album, Lux, was released yesterday. This latest project finds the Spanish singer, songwriter, and producer singing in 13 languages, including Catalan, Latin, Arabic, English, and her native Spanish: an invitation for listeners to stretch beyond their own linguistic comfort zones, connect through raw emotion, and, perhaps, learn some new forms of expression beyond their mother tongue(s). When co-host Joe Coscarelli (see the clip starting at 21:42) asks the Grammy Award–winner whether she feels like she’s “asking a lot of [her] audience to be able to absorb this,” referring to the album’s density, length, and built-in translation requirements, Rosalía replies, calmly and confidently, and without hesitation: “I think I am. Absolutely I am. But I think that the more we are in the era of dopamine, the more I want the opposite. That’s what I’m craving.” Rather than feel the need to overexplain, apologize for, or dilute her own artistry for the sake of surface-level, mainstream accessibility, she trusts her fans to walk alongside her into uncharted territory, believing that wherever they land on the other side will be worth it.

Rosalía’s desire to craft a multilayered album that compels people to focus, if only for an hour, and emerge in a mind-altered state—moved, haunted by a song, or experiencing some form of release—resonates with our ethos here at The Slowdown. As you’ll discover in this week’s offerings, we also recognize the value of making and sharing work that draws you in for a closer read, listen, or look.

On the latest episode of our Time Sensitive podcast, Spencer speaks with the James Beard Award–winning culinary historian Michael W. Twitty, whose deep research process and polyvocal perspective, as exemplified in his new cookbook, Recipes From the American South, fosters greater understanding of the richness and complexity of the region’s food history. Likewise, my conversation with RoseLee Goldberg, the founding director and chief curator of the nonprofit Performa, for our latest “Media Diet” (below), reveals research as a key ingredient in her two-plus-decade process of commissioning, developing, and showcasing adventurous works of live performance, often by artists working in that genre for the first time in their careers, as with Camille Henrot, whose first-ever performance art piece will premiere next year (listen to Ep. 140 of Time Sensitive to learn more about what the Paris-born, New York–based artist has in store). Through spending time with their ever-changing source material each year, RoseLee’s commitment to, as she puts it, “travel similar roads” with her artist collaborators allows her to build lasting relationships and spark new ideas that transcend her commission, long after each Performa Biennial ends (the current edition runs through Nov. 23).

Here’s to going deep, with whatever we’re drawn to—and, hopefully, being surprised and awed by what we find in those depths.

—Olivia

“Being intersectional and being multicultural means that I am working with different models of communication, different models of time, all the time. So, yes, it’s linearity, but also concentric circles, but also a spiral, but also a zigzag.”

Listen to Ep. 141 with Michael W. Twitty at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

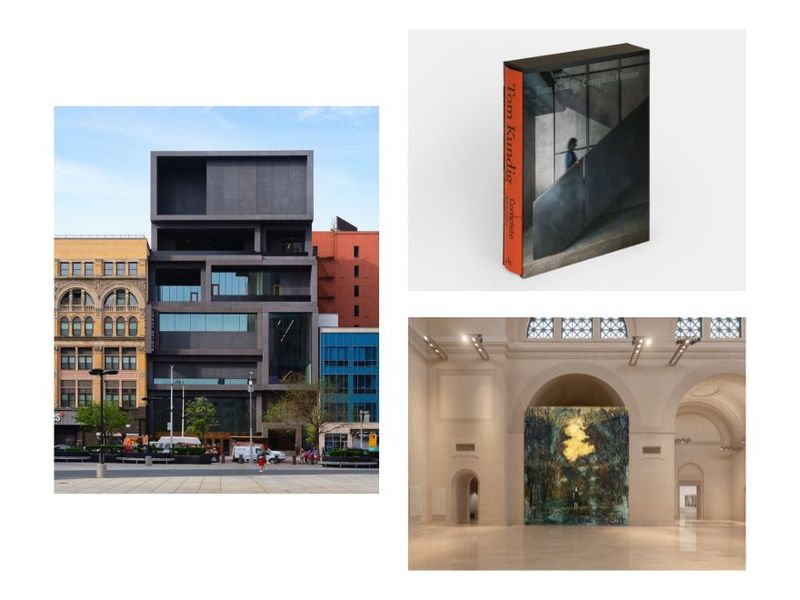

Studio Museum in Harlem

One week from today, the Studio Museum in Harlem will open the doors of its bold new seven-floor home with an all-day, community-centered celebration. As with the new Princeton University Art Museum, the unveiling of which we covered in last week’s newsletter, the building was designed by Adjaye Associates—whose founder, David Adjaye, was removed from the project in 2023 following sexual assault and harassment allegations—along with the firm Cooper Robertson. (Adjaye gave a rare interview to Architectural Record this week about the convergence of these milestone projects while also navigating his cancellation.) The new building, made possible by a $307-million capital campaign led by its director, Thelma Golden, forges a new path for this nearly 60-year-old cornerstone institution of Black creativity, culture, and craft, and stands as an energizing beacon for the next generation. As the architecture critic Michael Kimmelman (the guest on Ep. 14 of Time Sensitive) noted in a recent New York Times review, Golden and her team took care in keeping locals up to speed and well-informed during its construction process, which is a testament to her greater vision: that the museum play a meaningful role in the larger, ongoing effort to honor Harlem’s rich history, and that it enrich all who pass through its doors.

Tom Kundig: Complete Houses

A treehouse in Santa Teresa, Costa Rica, built entirely of locally sourced teakwood; a steel-clad cabin in the rainforest of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula; and an elevated ski house in the Coast Mountains of Western Canada all feature in Tom Kundig: Complete Houses (Monacelli), a new monograph dedicated to the Seattle-based architect’s sculptural, environmentally interactive approach. Presenting a chronology of 462 residential projects, including 12 previously unpublished homes, the book encapsulates how architecture can breathe fresh life into a place when its essential elements—space, light, material, and landscape—harmoniously come together. Original interviews between Kundig (the guest on Ep. 37 of Time Sensitive) and editor Dung Ngo delve into subject matter ranging from Kundig’s Swiss heritage to his hand-drawn sketches and photography practice. In 2027, keep an eye out for the companion volume, Tom Kundig: Complete Works, which will explore the influence of his residential designs across his non-residential projects.

“Anselm Kiefer: Becoming the Sea” at the Saint Louis Art Museum

In the German-born painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer’s first U.S. retrospective in more than two decades, the river evokes time’s ceaseless flow. On view through Jan. 25, 2026, at the Saint Louis Art Museum, “Anselm Kiefer: Becoming the Sea” presents around 40 works made from the 1970s to now, along with five monumental, site-specific installations. Recent paintings depicting the Mississippi and Rhine Rivers draw profound symbolic parallels between the two waterways, both among the longest rivers in their respective continents. Made with sediment of electrolysis, these verdigris and gold-leaf works incorporate female figures of water spirits and mark a subtle, lighter departure from Kiefer’s earlier works made with lead and clay. Curated by Min Jung Kim, with assistance from Melissa Venator, the exhibition reflects on the 80-year-old, post–World War II era artist’s nearly six-decade explorations of time, geography, and memory.

A willingness to surprise and be surprised runs through the media-intake habits of art historian, author, and critic RoseLee Goldberg, founding director and chief curator of the nonprofit Performa. Whether she’s delving into a Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of a leading Harlem Renaissance figure at the recommendation of an artist she has commissioned or revisiting a favorite archival arts magazine alongside the N.Y.U. students she teaches, Goldberg is deeply attuned to the kind of probing research and rigorous writing that takes artists’ boundary-pushing contributions to society seriously. Here, she shares the ways in which she keeps her finger on the pulse of art and culture, and what leading Performa for two-plus decades has taught her.

How do you start your mornings?

Raring to go. I can’t wait. In fact, I don’t think I sleep, because I get bored when I’m sleeping, and think of all kinds of ideas that I want to be moving on. Performa is a tiny-but-mighty organization. We’re looking at new media, we’re looking at magazines, we’re looking at ideas coming from all kinds of disciplines. Obviously, working with something like performance and my own background is gliding back and forth across all different disciplines. I sometimes think of it a bit like keeping plates in the air. I’m intrigued by architecture, dance, film, music, sound, poetry—how it relates to this moment in time and how we’re all changing and responding, not to mention everything else that’s going on in politics and so on.

You mentioned magazines. What are some titles of your favorites?

I still teach at N.Y.U., and I was just saying to my students this morning, “One of your assignments this week is to go to Printed Matter and look at different periods. Please make sure you put your hands on Avalanche magazine.” It was the first magazine of its kind to put a single artist on the cover of every issue. It’s so much about what was going on in conceptual art in the seventies: its refusal to have other people translate the work, this idea that the artist was in the forefront, the artist was in control of their own message, their own material, their own exhibiting, making their own work or presentation as needed.

How do you stay current?

I listen, I look, I watch, I question, I ask everybody I know. I keep an eye on what’s out there. I wrote [Performance: Live Art, 1909 to the Present] in 1979, and it’s something that has been updated all these years. It’s a huge exercise to look at all these different elements of the culture that are coming at us every minute of the day, and then to find a way to put all that material into one chapter. There’s always that sense of regret that you can’t possibly get to everything, or can’t possibly cover everything, but somehow, you’re trying to distill what’s out there. That’s the excitement.

Any favorite newsletters?

I’m actually impressed at the moment with the high level of newsletter writing, which says something about there being so few outlets. As much as we complain about the internet and digital, it’s almost as though there’s more writing than ever. It’s impressive writing, too. Again, I wouldn’t say I go to specific ones over and over again, because I’m trying to get a cross section and a range of ideas. I’m moving so fast between them. I’m skimming over a lot of different material and trying to analyze who is claiming what. I do greatly miss more of the elegant, very rich writing of some of the magazines that we’ve had in the past that no longer exist, or even missing somebody like [The New Yorker’s late longtime art critic] Peter Schjeldahl.

I’m still a great believer in a very rigorous kind of writing. I’m still teaching and trying to get students to pay attention. It’s much more immediate, of course, to stay up to date with the news, which they have to do, as well. But I also want them to recognize that sentence that contains so much information, how that was put together.

What was the last reading experience where you felt like you were getting lost or going into that quieter realm and living there for a period of time?

I couldn’t stop talking about The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke by Jeffrey C. Stewart. It’s a very detailed history of a Black philosopher from the early 1900s. It was a period of wonder, reading that book, because I felt it was taking us into histories that I thought I knew the general outline of, but really had no clue about how intricate they were. Every page was a revelation. Then, of course, it tied to the extraordinary work that Isaac Julien made about [Alain] Locke and the Barnes Foundation and so on. You’re suddenly going back and forth between all these different histories and really seeing how different artists can take history and bring it into the middle of our conversation.

After two decades of leading Performa, what’s something that continues to surprise you in the process of supporting artists and helping them realize their visions each year?

That individual enlightenment that each one provides. They turn on lights that you had no idea about. They’re touching every kind of form of perception that you can imagine. Let’s just say you’re looking at something for an hour: You’re looking at an artist’s visual aesthetic. There is a sensibility that comes across. You’re hearing sound; you’re seeing where an artist is finding a way to animate and illuminate what they’re working on. Even the venues we find: To me, the idea of the venue is like the perfect frame. You’re putting a work in a context that actually is going to complement their thinking and somehow expand on it and give it a surprising beauty. You’re commissioning somebody to do a work who hasn’t done performance before. All these things are raw, and they’re right in front of you. It’s a deep sense of getting as close as possible to watching ideas unspool and respool and come out in so many different shapes and forms.

The artist Diane Severin Nguyen mentioned in a recent New York Times piece that her Performa commission marked the first time she’d worked without “a camera between me and a person.” It’s cool that Performa’s commissions allow artists to step into a physicality or embodiment that they may not have previously experienced or explored.

That’s the wonderful part about Performa: hearing an artist talk about what it opened up to them. Rashid Johnson [the guest on Ep. 25 of Time Sensitive] saying that, actually, it took him into making a film [Native Son], because he realized how much he enjoyed directing. It’s that long tail of what happens afterwards that really is fascinating. Even years later, to have people still talk about that moment: It’s really wonderful to watch that magic place.

This interview was conducted by Olivia Aylmer. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

The Spector Craft Prize, launched this month and with applications opening on Nov. 11, celebrates what jury chair Glenn Adamson (the guest on Ep. 50 of Time Sensitive), calls “the role of craft as a vital and enduring force in our culture.” [Spector Craft Prize]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new culinary partnership with chefs Rita Sodi (the guest on Ep. 116 of Time Sensitive) and Jody Williams will add yet another reason to visit. [Eater]

In an interview about her remodeling of the British Museum’s Western Range, Lina Ghotmeh (the guest on Ep. 129 of Time Sensitive) discusses how the project has been above all one of “reconstructing [the museum’s] history and trying to understand its essence—what must remain and what can be transformed.” [The Art Newspaper]

Author and poet Claire Phillips speaks with author Jonathan Lethem (the guest on Ep. 121 of Time Sensitive) about his latest collection, A Different Kind of Tension: New and Selected Stories, and his playful, immersive style across his fiction and arts writing alike. [The Brooklyn Rail]

In “Unfurling the Spiral,” a talk by executive editor and Sufi teacher Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, he examines the seasons’ cyclical nature and how they draw us into deeper kinship with the earth. [Emergence Magazine]