In this week’s newsletter, we speak with Ronan Day-Lewis about his debut feature film, Anemone; explore the recently opened Museo Casa Kahlo in Mexico City; flip through a book celebrating singular New England inns; and more.

Good morning!

The other week in London, for our latest “site-specific” episode of Time Sensitive, I had the absolute joy of sitting down with the author and cultural critic Olivia Laing for a wide-ranging conversation on the pleasures, possibilities, and profundities of gardens (as the author of the exquisite, mind-expanding book The Garden Against Time, recently out in paperback, they are an expert on the subject); the notion of “garden time”; and the need for utopian thinking. We met up inside their apartment in the brutalist gem that is the Barbican, which definitely stands out as one of my favorite “studios” I’ve ever recorded in, right up there with Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut (Ep. 119), and the Sanso Villa at the George Nakashima Woodworkers compound in New Hope, Pennsylvania (Ep. 101). (I’m off to Chicago in a couple of weeks for our next site-specific recording, and can’t wait to share it with you all soon.)

I’m sure many of you reading this know of Olivia’s work, but for those who don’t, they are the author of several fiction and nonfiction books, including 2020’s Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency and—their critically acclaimed breakout—2016’s The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone. Their next title, the novel The Silver Book, comes out in the U.S. on Nov. 11.

My interview with Olivia reminded me once again just how important it is, in our frenzied, chaotic, content-overload age, to take time to pause and ponder and, yes, slow down, but also—most importantly—to get into deep dialogue. To talk with Olivia was, in some sense, to be in a garden with them, digging. Many of us, myself included, often take conversation for granted. We can all too easily forget the magic and wonder to be found in an unhurried exchange. To be in dialogue is to plant seeds and watch them grow.

I know I’m preaching to the choir here (and I realize that hosting a podcast helps me do this in ways I wouldn’t necessarily be able to otherwise), but even I sometimes need a reminder of how unquestionably transformative conversation is to our very being. Simply put: Conversation is essential to who we are. Conversation is key to feeling the “aliveness” that Oliver Burkeman recently spoke with me about on Ep. 137, and—I’m sure that Olivia would agree with me on this—it’s also an antidote to the loneliness creep so prevalent in our social media–fueled world.

While we live in an isolating era, no question, it doesn’t have to be that way. Humans are social animals, after all. We just need to more actively engage our conversation muscles. For me, Sherry Turkle’s 2015 book Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age proves this out. A bible on the subject, it has only become more essential over the decade since it was published. Vuslat Doğan Sabancı’s Generous Listening project comes to mind here, too.

Not surprisingly, meaningful dialogue is embedded in all that we do here at The Slowdown, and this week’s “Interview With,” below, exemplifies this. Our very own Olivia (Aylmer) has a beautiful exchange with the painter and filmmaker Ronan Day-Lewis about his new movie, Anemone. She refers to a certain moment in the film as “balletic,” and I’d describe her conversation with Ronan the same way.

May we all have more beautiful, balletic conversations in our lives.

—Spencer

“The garden clock really has something to tell us, and that something is that we have to allow ourselves to move through these cycles of rot and decay and almost nothingness before coming out the other side.”

Listen to Ep. 138 with Olivia Laing at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

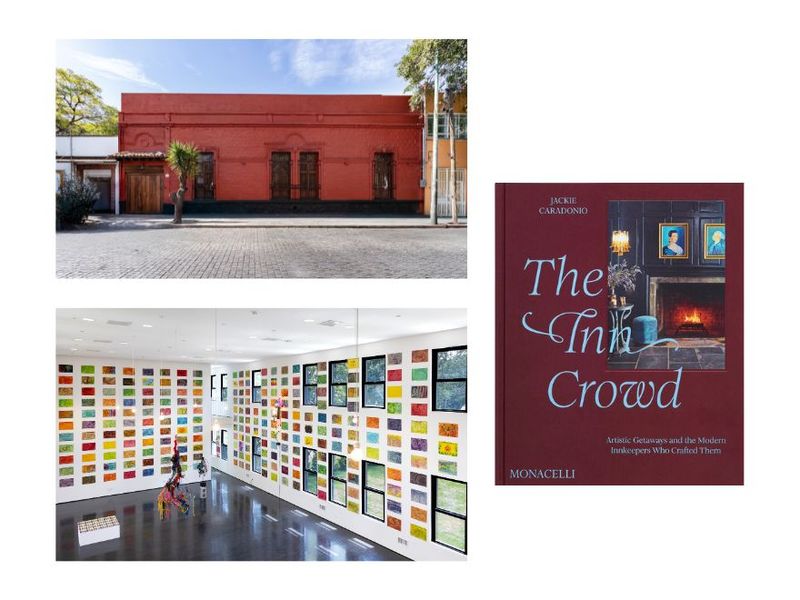

Museo Casa Kahlo

Rarely does the public get a glimpse of Frida Kahlo the person, rather than just Frida Kahlo the artist. Now, with the recent opening of Museo Casa Kahlo in Casa Roja, a private residence acquired by Kahlo’s family in 1930, a fuller portrait of Kahlo is emerging. Located in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City, mere blocks away from her famous family home, Casa Azul, the museum offers a window into the artist’s private universe, such as the preserved kitchen containing Kahlo’s only known mural, and a room embodying some of her most enduring commitments: on one side, La Ayuda—her sister Cristina’s charity for single mothers, based at Casa Roja in the 1950s—and on the other, “Los Fridos,” her devoted students. The New York–based firm Rockwell Group led the experience and exhibition design, including the courtyard and basement space, which, for the first time, recreates Frida’s hidden, ephemera-filled studio for the public. The museum also plans to feature rotating displays of contemporary work, with a focus on fellow Mexican, Latin American, and female artists, as a way to elevate current perspectives that build on Kahlo’s legacy.

The Inn Crowd

A wanderlust-inducing guide to exceptionally crafted homes away from home, journalist and photographer Jackie Caradonio’s new book, The Inn Crowd: Artistic Getaways and the Modern Innkeepers Who Crafted Them (Monacelli), presents 20 independent inns across the American Northeast—paired with vivid portraits of the innkeepers who, in many cases, left illustrious careers in fashion, media, medicine, and tech to pursue their hospitality dreams. Among the featured properties is The George, beauty magnate Bobbi Brown and her husband, Steven Plofker’s, 31-room hotel in a landmarked Georgian Revival building in Montclair, New Jersey; the Inn at Kenmore Hall, former J. Crew menswear designer Frank Muytjens and his partner, Scott Edward Cole’s, 19th-century Berkshires estate; Inns of Aurora, the American Girl dolls company founder Pleasant Rowland’s collection of restored historic guesthouses in New York’s Finger Lakes region; and The Roundtree at Amagansett, former tech attorney Sylvia Wong’s homey hideaway in the heart of the Hamptons. Captured through Caradonio’s immaculate lens, details of the inns’ architecture, art collections, culinary offerings, and landscaping delight the senses—and may even set an autumnal or early-winter weekend getaway in motion.

“Upside Down Zebra” at The Watermill Center

An imperfect circle, a spiral line, a zigzag, a dot: To the pioneering early childhood scholar and educator Rhoda Kellogg, these markings were more than mere scribbles; they were keys to understanding the nascent human mind in formation. “Upside Down Zebra,” an exhibition on view at The Watermill Center (founded by the late avant-garde theater and visual artist Robert Wilson, the guest on Ep. 96 of Time Sensitive) through Feb. 15, 2026, puts approximately 900 children’s artworks from Kellogg’s collection of two million–plus drawings from around the world in imaginative dialogue with works by more than 35 contemporary artists including the painter and self-described “sculptor of creatures” Alake Shilling; Misaki Kawai, known for her spirited paintings, sculptures, and papier-mâché works; and the painter Carroll Dunham, whose fantastical, abstract-meets-figurative style has, over the past four decades, drawn inspiration from cartoons, surrealism, and science fiction. Co-curated by child art enthusiast and multimedia artist Brian Belott (long devoted to uplifting Kellogg’s contributions in art and education alike) and curator Noah Khoshbin, in collaboration with educator Jennifer DiGioia, this playful, intergenerational celebration of instinct, improvisation, and uninhibited experimentation also includes public programming for all ages to appreciate.

While developing Anemone, Ronan Day-Lewis’s psychologically haunting debut—co-written by and starring his father, the formidable Daniel Day-Lewis, in a welcome onscreen return after eight years—the 27-year-old filmmaker and painter pinpointed silence as one of the film’s guiding principles. Initially, there was even talk of the entire story unfolding sans dialogue. The estranged brothers (Ray, played by Daniel, and Jem, played by Sean Bean) at the heart of his film do, eventually, exchange words and deliver their fair share of illuminating monologues, which are further intensified by the British musician and producer Bobby Krlic’s score. Still, Ronan makes a deliberate point of withholding as much as possible for the first 30 minutes, preferring to let negative space, nature’s elemental power, and the tension of compounding truths left unspoken over many years establish the tone for this deeply felt human drama.

Drawing on his experience as a brother himself, Ronan deftly explores familial quick swerves: from love to rage, shame to anguish, and back to love. In one particularly striking scene, Ray and Jem exorcise their respective demons through wordless movement, swiftly shifting from ecstatic solo dancing to playfighting in the blink of an eye—the kind of moment that could be written only by someone who understands the near-telepathic connection that can form between siblings, no matter how much emotional, temporal, or geographic distance has come between them.

Last Monday, the morning after Anemone’s world premiere at the New York Film Festival, we caught up with Ronan to discuss his directorial debut.

So much of Anemone’s unsettling, mysterious tone comes from the distinct lack of dialogue in the first thirty or so minutes. What role did you want silence to play in telling this story of, as you’ve called it, the “beauty and tragedy” of brotherhood?

Silence was so important to us from the beginning. We almost originally set out for the whole film to be silent. Then, we held out for a certain amount of time, and I think maybe that’s what made for that outpouring of speech. It was interesting finding the rhythm where we could test how long we could hold some of those silences, both within certain scenes and over the course of the entire film. It’s almost like the film is holding its breath. There’s this sense of storm clouds congealing and coming together. Eventually, the silence is broken in an intense way. But silence was definitely a guiding star for us.

In that first scene of reunion between the brothers, there’s this fascinating choreography in how they move around each other in the room—it’s almost balletic. How did you arrive at that?

Yeah, the hut became this kind of landscape, this stage, for them. I like the way you talk about it as balletic, because every day, we’d talk through the next day’s scene in terms of how they’d move around each other through the space. That really informed the production design, too—where the furniture was arranged, where the bed had to be in relation to the stove, and where the arm chair that Jem sits in had to be in relation to the table. There are these moments where they’re kind of forced into this uncomfortable proximity. Then, at times, there’s this distance between them, despite the claustrophobia of the setting. It was about letting the blocking communicate their inner lives and their constantly fluctuating feelings toward one another and the volatility of that relationship.

Thinking a bit beyond that claustrophobic space to the natural world, I would love to hear about how you incorporated nature and weather—both its breathtaking beauty and its destructive potential. There are many examples of this: the near-Biblical hailstorm; the overhead shots of swaying treetops; and the gigantic silver fish, an almost mythological creature.

From the beginning, even in the first ten pages of the script, it felt like the weather—the rain and the wind and the elements—served a purpose beyond just setting a mood and an atmosphere. There’s this sense of nature both continuing on, indifferent to human anguish and the human struggle at the forefront of the story, and then in concert with that, at times. A silent question throughout the film is whether these elements are responding to the human drama that we’re seeing. They give it this cosmic backdrop at times, where it’s this very intimate story, but the weather allows it to go beyond that, into more of a mythic realm.

I’d love to hear about the sound design.

I worked with this amazing sound designer, Steve Fanagan. In those moments of negative space and silence, the sound design ended up basically being the dialogue. There’s this constant awareness of the outdoors and of something bigger than the intimate drama we’re seeing unfold in front of us.

We spent months trying to find the perfect wind sound—that kind of whistling, old-fashioned wind—that felt like it had that spiritual quality. We looked at [the David Lynch movie] Blue Velvet, moments in hallways, these transitional moments where there’s this subterranean sound that’s blended with the wind. And then there’s this scene in [the Federico Fellini film] 8½ where they pull up into an empty alleyway, and the only sound is just this whistling wind. It creates this atmosphere that’s impossible to get any other way.

Whether consciously or not, how did your visual art practice inform your vision for the film’s look and feel?

Having had the last few years to dial in to a visual language in my paintings, I think it was so important, both to help myself and to communicate to my collaborators. A lot of it was unconscious, in terms of certain images that I’ve always been drawn to in painting, very obsessively, that ended up making their way into the film. But also atmospherically and tonally, I tried to think of the two increasingly as not necessarily separate, but just two different expressions of the same impulse. Having the images move and sound being a possibility in film—it felt like a really thrilling extension of painting.

Anemone marks your first feature film collaboration with your dad. Growing up, do you recall any moments of more informal creative collaboration with him that helped inform your work together on this larger-scale project?

Yeah, we’ve always made things together. I did this art installation for my thesis show in college, where I showed paintings, but also this sculptural element with all these fabric snakes. My dad had the skill to help me sew those. That was a really fun experience.

He also mentioned something that I’d completely forgotten about the other day. When I was around 5, we made this book together with all these illustrations I had done of this octopus character navigating an underwater world. He made a cover for this bound book with swim shorts, so it had a pocket on the cover. I also made this massive sculpture a couple years ago of the creature that actually appears in the film—this two-hundred-pound wax sculpture. I had all the pieces of the infrastructure for it, these wood and foam pieces that had to fit together. He helped me assemble that, because it was this massive, unwieldy thing.

Aside from the obvious fact that he’s one of the greatest actors alive, why did you feel that your dad was the right person to portray this particular character and story?

I mean, there was never any question. It was always our aim to find something that he could act in and that I could direct. Conjuring the script was such a unique experience. In the past, I’d written scripts on my own where I’d gone in with a really detailed outline. You end up forcing the characters into certain decisions that you realize, in retrospect, don’t add up; it creates these problems structurally. Whereas, with this, he [Daniel] was really becoming Ray over the course of this process. It was so intuitive and so real from an earlier stage. Growing up, I, like everyone else, I guess, have been in awe of his work. Seeing him go into these worlds was always very mysterious to me as a kid—sort of being a bit behind the curtain and absorbing a bit of that mythology, in the way that the world seemed to look at him. Seeing that process from such a different vantage point was such a remarkable experience.

This interview was conducted by Olivia Aylmer. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

In “Finally, Something Good,” on view through March 1, 2026, at the Museo de Arte de Zapopan in Guadalajara, Mexico, Stefan Sagmeister (the guest on Ep. 8 of Time Sensitive) presents a series of graphic design and data visualization works that challenge and offer alternatives to what he views as an overreliance on dystopian narratives. [Museo de Arte de Zapopan]

What Is War, a fusion of movement, video, and personal testimony on from Oct. 21 through 25—created and performed by Eiko Otake, who grew up in postwar Japan, and Wen Hui, who grew up in China during the Cultural Revolution—explores war’s lasting impact on human consciousness, collective memory, and the body. [Brooklyn Academy of Music]

The recent full-house launch of author Francesca Wade’s book Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife, at Manhattan’s Paula Cooper Gallery (thankfully recorded for posterity) convened a potent group of poets, writers, and musicians, including Laurie Anderson, Erica Hunt, and Eileen Myles, to pay tribute to the larger-than-life 20th-century literary figure and salonnière. [192 Books]

“A Taste of Beauty,” on view through Jan. 11, 2026, at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California, examines African sculptural traditions through spoons (made of wood, gourd, bone, and metal) as a means to understand and tangibly connect with people and communities of the past. [The Crocker Art Museum]

In an interview with the Columbia Journalism Review, writer and journalist Matthew Shaer, the host of several long-form podcasts, including the recently launched Origin Stories, talks about why he believes that, even though we’re past the initial podcasting boom, “good storytelling will find a way.” [Columbia Journalism Review]