In this week’s newsletter, we ponder the many meanings of culture, check out Sky High Farm’s inaugural biennial, catch up with Sanford Biggers at the Donum Estate in Northern California, and more.

Good morning!

As I mentioned in last weekend’s newsletter, this week marks the release of Culture: The Leading Hotels of the World (Monacelli), the second book in an ongoing series edited by The Slowdown (read more about it in Three Things, below). And while it’s of course a book about the independent luxury hotel group, it’s also no typical brand book. Being the word nerd that I am, making this book was, for me, an opportunity to dig into the definition of the word culture—a subject I’ve thought a lot about over the years, but never spent concerted time truly delving deep into.

What I discovered, as I note in the book’s introduction, is that culture is, has been, and always will be an extraordinarily complex word. Its etymology goes back to the Latin terms colere, meaning “to inhabit, care for, till, worship,” and cultura (“growing, cultivation”), and its modern-day usage stems most directly from the writing of the ancient Roman poet and philosopher Cicero, who, around 45 B.C., made note of a “cultura animi,” or a cultivation of the soul. In Middle English (written and spoken around 1100 to 1500), the word came to mean “place-tilled,” and—fast-forward 300 or so years—in the 19th century, it came to refer to a certain ideal of human refinement.

For me, the British philosopher and poet John Cowper Powys’s definition of culture as “a pilgrimage” is the one I like best. For, in today’s globalized world, to be cultured means to have traveled, whether literally or in our minds, across continents, cities, and constellations, via art, music, food, fashion, film, literature, poetry, sport, dance, craft, architecture, and beyond. Culture is, at its heart, about discovering and experiencing in great depth worlds and realms—whether close to home or in a faraway land—and through that process, growing.

Appropriately, I was in Portugal this week to launch the book at an LHW summit, visiting two extraordinary Eduardo Souto de Moura–designed properties there, Bairro Alto in Lisbon and Saõ Lourenço do Barrocal in Monsaraz. At the latter, I led a conversation with José António Uva, who transformed his eighth-generation, 200-year-old family estate in the Alentejo countryside into a 40-room hotel, which opened in 2016; the British-born photographer Mark Borthwick, who lives 20 minutes down the road and made the pictures for the feature story in Culture on Barrocal; and the Lisbon-based architect, artist, and designer Joana Astolfi, who created a cabinet of curiosities–style installation in Barrocal’s restaurant.

In our wide-spanning conversation, the thing that moved me the most, perhaps not surprisingly, was a poem. Borthwick, ever the free spirit he is, pulled out a piece of paper with a three-stanza poem he’d written as an ode to the culture of Barrocal and Alentejo. The third stanza reads: “In the Spirit of Affinity / Barrocal’s the Heart of Its Community / Its Majestic Beauty’s Equanimity / Reflects Its Staffs Benevolent Intimacy / Its Welcome Sign Entwines / Dear Mother Nature’s Refining Eye / Its Embrace an Escape of the Mind / Its Soul the Heart of Our Time.”

“Benevolent intimacy” strikes me as one of those things we all want more of in our lives, but that all too often seems so difficult to find. At Barrocal, I’ve felt that and more, fully embracing the sense of slowness that pervades the place. Culture there starts in the soil, right where the word’s etymology did centuries ago.

—Spencer

“That’s the only lesson I think that has any value in aging: Design your life to bring you the most peace and joy that you can possibly do.”

Listen to Ep. 135 with James Frey at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

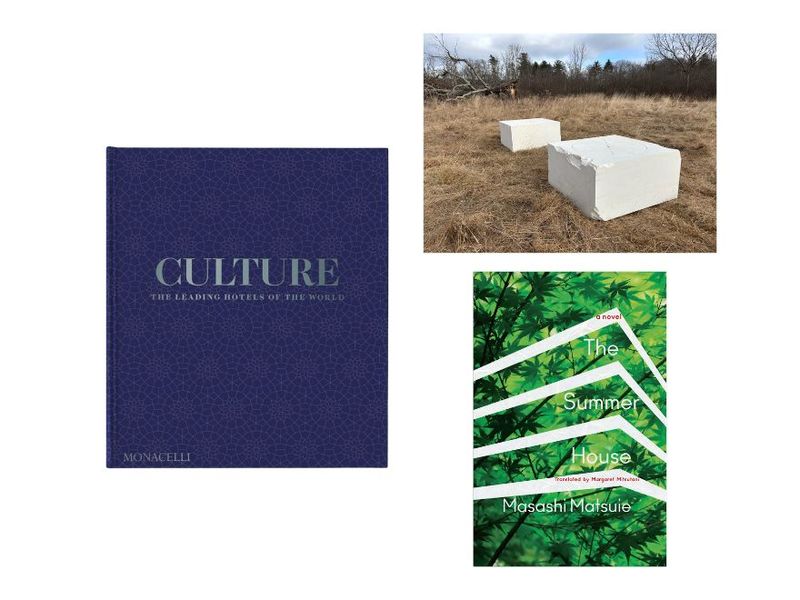

Culture: The Leading Hotels of the World

At the De L’Europe Amsterdam hotel, tulips and burnt-orange velvet curtains provide an opulent Dutch foreground for a museum edition of Vincent Van Gogh’s famed “Sunflowers” painting. A lush Indonesian jungle dominates at the Capella Ubud in Bali, prompting visitors to lean on bamboo walking sticks as they venture out to their private hideaways. Local pottery is central to São Lourenço do Barrocal in Portugal, where roughly 350,000 terra-cotta bricks were fired nearby and installed. These are just a few of the more than 80 exquisite properties that feature in Culture: The Leading Hotels of the World (Monacelli), the second book in a multivolume series with editorial direction by The Slowdown. Highlighting each hotel’s distinctive cultural attributes, from ancient craftsmanship and mouth-watering local dishes to sublime natural landscapes, the book opens with a foreword by the acclaimed Kyoto-based travel writer Pico Iyer (the guest on Ep. 127 of Time Sensitive) and includes six feature stories, an in-depth conversation between the jewelry maker Solange Azagury-Partridge and the designer Tom Dixon (the guest on Ep. 94) at Brown’s Hotel in London, and an interactive Index with insider tips from the likes of the craft-forward Deborah Needleman (the guest on Ep. 66), Marlies Verhoeven of The Cultivist, and the artist Bosco Sodi. Designed by the award-winning graphic designer Michael Bierut (the guest on Ep. 81) with Jena Sher, this volume is a rare window into how local touches, age-old rituals, and international art serve exceptional hospitality.

Sky High Farm Biennial

Opening today in Germantown, New York, inside a historic apple cold-storage warehouse along the Hudson River, is Sky High Farm’s inaugural biennial, “Trees Never End and Houses Never End,” a site-specific exhibition exploring the relationship between local ecology, history, and industry in the Hudson Valley and its connection to New York City. Founded by the artist Dan Colen (the guest on Ep. 40 of Time Sensitive), Sky High Farm is a nonprofit organization that responds to urgencies in the food system by growing and donating food to local food banks and pantries, and, more broadly, addressing the interconnection of nutrition security; economic and health disparities; and the history of structural, racial, and educational injustice. The biennial brings together works by more than 50 artists from around the world, including Mark Armijo McKnight, Nan Goldin, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Anne Imhof, and Rirkrit Tiravanija, to explore themes close to Sky High Farm’s mission, with a portion of proceeds being donated to the farm. On view through October, the presentation alludes to what’s possible when art, agriculture, and activism function as one—uniting the culture-shifting work of artists and the impact of a justice-driven organization.

The Summer House

The Japanese author Masashi Matsui’s debut novel, The Summer House (Other Press), offers an insightful portrait of modern Japan through a group of architects competing to design a major new building in Tokyo. Beginning his literary career as a fiction editor for the Shinchosha Publishing Company, where he worked with acclaimed writers such as Yoko Ogawa, Banana Yoshimoto, and Haruki Murakami, Matsui later launched Shincho Crest Books, an imprint specializing in translations of foreign works. The Summer House was first published in Japanese in 2012 and won the prestigious Yomiuri Prize for Literature, but it wasn’t until this year that he at last published it in English. Beautifully translated by National Book Award winner Margaret Mitsutani, the novel follows Tōru Sakanishi, a sensitive, observant university graduate who joins the Murai Office, a small architecture firm founded by a former student of Frank Lloyd Wright (the character, Shunsuke Murai, is loosely based on Junzō Yoshimura, who had once been a protégé of Antonin Raymond). As the sweltering summer months approach, the Murai Office migrates from Tokyo to the mountain village of Kita-Asama. There, the team sets out to design a national library, competing against a rival firm that snaps up one government project after the next. Aptly titled, The Summer House is the perfect summer read that portrays the natural beauty of Japan, the craft of architecture, and the dissonance between modernity and tradition.

Within the rolling hills of the Donum Estate, art collector Allan Warburg’s Sonoma vineyard and sculpture garden, the artist Sanford Biggers (the guest on Ep. 99 of Time Sensitive) recently introduced the winery’s latest acquisition: “Oracle” (2021), a 25-foot-tall sagacious, Sphinxlike figure cast in bronze. Seated in a stately position, it has both the body and torch of Zeus at Olympia, a long-lost Greek sculpture that experts date back to the fourth century B.C., and a monumental head roughly the same size as its body, with mysterious half-closed eyes.

“Oracle”’s enigmatic expression lies somewhere between transcendence, judgement, and possibly boredom—and according to Biggers, that ambiguity is exactly the point. Dodging “aesthetic or conceptual expectations,” he tells The Slowdown, the sculpture designates the task of interpretation to the audience. Unanswered questions have a way of stoking the imagination and encouraging more active viewing, he adds. “People have to figure out some meaning for themselves.”

Having originated as an Art Production Fund commission, “Oracle” debuted at Rockefeller Center in 2021 and traveled to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles before joining Warburg’s collection. Now in the company of other on-site works by the likes of Anselm Kiefer, Yayoi Kusama, and Ai Weiwei, “Oracle” cuts an especially striking figure in this vineyard setting. Its unusual face combines the features of various African masks, including those of the Luba Kingdom and Maasai traditions. Biggers’s syncretic practice is full of beguiling composites like these—textiles, installations, and objects that combine the cultural symbols of African sculpture, Black American culture, Japanese Buddhism, and Greco-Roman art. In fusing these disparate sources, Biggers says, “What I’m ultimately trying to do is create new mythological objects. You can’t trace it to any one place, so in essence, it’s its own unique thing.”

Where appropriation is “considered a bad word,” the artist adds, he recognizes the merging of cultures as the inevitable throughline of human history. “I don’t think cultures move forward without borrowing and learning from each other.” Intent, he proposes, is what separates homage from exploitation.

In the windswept terrain of Northern California’s wine country in mid-June, he prepared a syncretic ritual in honor of the spiritual origins of sculpture, where masks were created to summon divine energy, and statues provided objects of devotion. Before an audience of art collectors, curators, dealers, and enthusiasts, he performed with Moon Medicin, his experimental Afrofuturist musical quartet, dressed in all white and wearing sparkling masks studded with crystals. They circled “Oracle” chanting a spiritual invocation, while a vocalist sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a hymn of optimism cherished as the Black American National Anthem. Shifting gears, a Buddhist abbot then led the audience in a moment of silent meditation.

Underscoring the universal role of art amid life’s mysteries and the eternal human search for meaning, Biggers closed out the ritual by asking us to leave “Oracle” an offering. (Before the performance began, we were offered a selection of small objects—bells, maracas, and other instruments.) “As you place them around ‘Oracle,’ leave intention and thought and introspection,” Biggers said. “With that, a blessing for all of you here, a blessing for the world. We need all the help we can get.”

—Janelle Zara

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

L’École, School of Jewelry Arts, supported by Van Cleef & Arpels—our longtime presenting sponsor of Time Sensitive—is launching a multilingual series of books themed around jewelry and the pleasure of collecting, signifying “luxury’s latest cultural shift” according to writer Milena Lazazzera: a focus on literature [Wallpaper]

The geologist Marcia Bjornerud (the guest on Ep. 123 of Time Sensitive) explains why pyrope garnet is arguably the most important mineral on Earth [Noema Magazine]

For his first Milan show, the fashion designer Paul Smith (the guest on Ep. 109) debuted a hot-weather line featuring lightweight tailoring, military touches, and spice-market colors [WWD]

In collaboration with the Copenhagen-based color and surface collective Blēo, the British architect and designer John Pawson (the guest on Ep. 130) has created Whitescale, a color palette of 14 “perfect white” hues, including marble, milk, and salt [Dezeen]

Katie Paterson, a Scottish artist known for her research-based works about Earth and the great vastness beyond, shrinks the universe down to human scale with two new shows in England [The New York Times]