In this week’s newsletter, we speak with herbalist Rachelle Robinett about her new book, Naturally: The Herbalist’s Guide to Health and Transformation; pay a visit to a sculptural installation at an Oregon winery; and more.

Good morning!

Olivia Aylmer here, stepping in for Spencer as he prepares to head to Aspen for the inaugural AIR festival (learn more about it in our July 12 newsletter, if you missed it) and then take a late-summer 40th birthday pause. As August will mark my second full month stepping behind the scenes at The Slowdown as senior editor, I thought I would take a moment to say hello.

Having arrived at this role after a (frenetic!) decade of media and publishing jobs of varying speeds, there’s something immensely refreshing and grounding about working alongside people who believe in building something slowly, steadily, and with immense care imbued in every detail. As someone who seeks out thoughtfully crafted and generously shared work in whatever form it takes—the kind that only grows and deepens in meaning, beauty, and value over time—I’m excited to have found kindred collaborators, readers, and listeners in all of you. In a forthcoming issue of our newsletter, I’ll share more about the media that keeps me energized, nourished, and excited to keep making things that last.

Joining The Slowdown is already bringing me into contact with people I deeply admire who share this sensibility—like the legendary avant-garde theater and visual artist Robert Wilson (the guest on Ep. 96 of Time Sensitive). Earlier this week, I spent a day on Long Island’s East End at The Watermill Center, which Wilson founded in 1992 as a space for co-creation, research, and discovery among an ever-growing community of multidisciplinary artists. From sharing a lively alfresco pasta lunch with several dozen visiting artists-in-residency, to taking in Wilson’s array of objects, books, and artwork—a still-growing “living entity” of almost 8,000 works—to catching glimpses of artists around the campus rehearsing for this weekend’s summer benefit, it’s the kind of space you could wander through for a lifetime and never grow bored. As a former dance student and devoted supporter of the art form, it was a particular pleasure to witness a mesmerizing work in progress from Belgian dancer and choreographer Cassiel Gaube, supported by a Van Cleef & Arpels Dance Reflections fellowship, which builds on the high jewelry maison’s mutually generative, decades-long relationship with the dance world.

As Gaube performed on an outdoor stage, dappled with midafternoon sunlight, and a soft wind rippled through Watermill’s surrounding trees and sculptures, I was reminded of my recent “Interview With” conversation with herbalist Rachelle Robinett, below. Midway through our call, Robinett’s attention briefly turned to the tree outside her window, while I appreciated the delicate window-box flowers beginning to bloom outside my own, and we spoke about just how close we are to deepening our relationship with nature, even in these small moments—if only we stay curious about what it has to teach us. I’m looking forward to absorbing even more of Robinett’s invaluable new book, Naturally, in which she offers an accessible, practical starting point for how to incorporate the wisdom and healing properties of plants into our day-to-day lives—and, in so doing, reconnect with and honor centuries of Indigenous-led knowledge and practices.

This week, I hope you also carve out some time to slow your pace, however briefly, and notice what’s right in front of you.

—Olivia

“A building that is truly timeless is a building that makes us look at the world in a new way, and that way continues to be meaningful long afterwards.”

From the archives: Listen to Ep. 119 with architecture critic Paul Goldberger, recorded inside the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, on July 10, 2024, at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

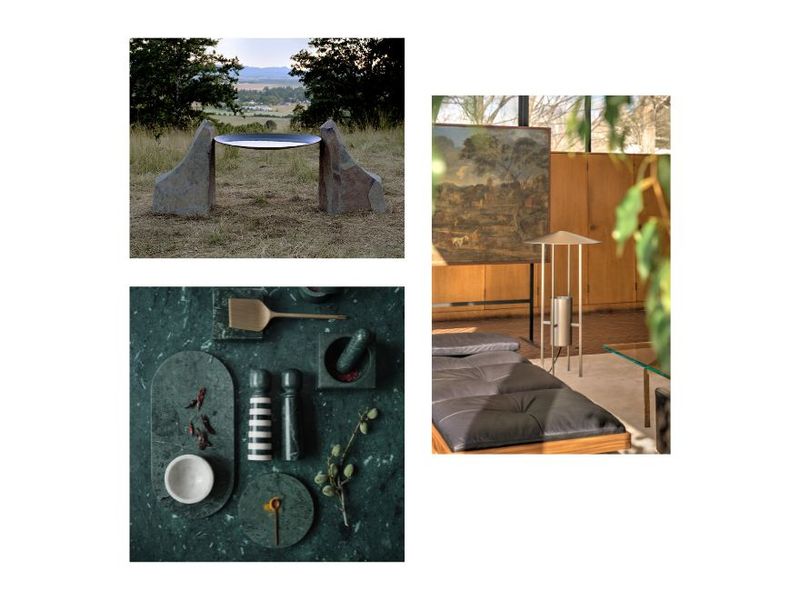

“Slip Condition” at Antica Terra

Nestled within the 88-acre grove of the Antica Terra winery in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, “Slip Condition,” a site-specific installation of sculptures by the Los Angeles–based artist Lily Clark (on view through Aug. 31), explores water and its relationship to both natural and human-made surfaces. A collaboration with the L.A. gallery Marta, the exhibition—named for the boundary state in fluid dynamics in which liquid flows along a surface with only the slightest resistance—examines water in a liminal state. Through these works, water is encouraged into its various forms (droplets, pools, streams) by the use of carbon-based synthetic materials, then juxtaposed with its interactions with mafic volcanic stones including basalt, scoria, pumice, and obsidian, all native to Oregon’s rocky landscapes. As visitors move along the path through the trees, they will see a series of small liquid works held on cedar plinths, which are coated in a superhydrophobic substance. Further along, they will find more substantial works where water is guided and reshaped by polished basalt and carbon-rich powder coatings. Drawing on her deep knowledge of fluids in flux, and with her keen eye for shape and form, Clark proposes a new understanding of sculpture’s possibilities by playing with the behavior of one of earth’s most basic and essential elements.

Johnson/Kelly Lamp (1953), Reissued by Bassam Fellows

When Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, was completed in 1949, it transformed the way people experienced architecture. Both outside and inside this Modernist glass box, everything is made visible, from the colors and textures of the surrounding woodlands to the daybed designed by Johnson’s mentor, Mies van der Rohe. When night fell, however, the architecture presented a conundrum: Due to the reflectiveness of the glass and the absence of interior walls, traditional lighting simply didn’t work. After initially using a tall candelabra lamp, which Johnson found unsatisfactory, he sought out the lighting designer Richard Kelly to devise a better solution. Drawing on his knowledge of stage lighting, Kelly helped design a lamp that reimagined the conventional approach. Instead of overhead lighting, the floor lamp featured a high-wattage bulb concealed by a conical shade, thereby reflecting the light downward and inward. The result was a warm, glowing pool of light that subtly illuminated the living area without casting harsh reflections. First produced in 1953, the design would go on to appear in home interiors commissioned by some of that era’s most significant art collectors and join the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. This year, the furniture and design house Bassam Fellows is reissuing the lamp, out of production since 1967. Unveiled at the 3 Days of Design festival in Copenhagen this summer, the lamp will be available this October via the Bassam Fellows website as well as through Design Within Reach.

Daniel Humm x Crate & Barrel Collection

Montreux wine glasses handblown by a team of nine expert glassmakers in Portugal, a recycled stoneware salad plate, and a eucalyptus-green Staub cocotte fitted with a brass ginkgo leaf knob all feature in the new Crate & Barrel collection, created in collaboration with acclaimed chef and restaurateur Daniel Humm (the guest on Ep. 53 of Time Sensitive), the visionary behind Manhattan’s three-Michelin-starred Eleven Madison Park. Drawing inspiration from the Swiss-born Humm’s love for the Bauhaus movement, the collection features more than 30 pieces made for modern kitchens that combine the chef’s minimalist eye with Crate & Barrel’s tried-and-true designs. Primarily crafted from green marble, stone, glass, and wood—including walnut, white oak, and beechwood—the pieces enhance dishes, complementing their natural hues rather than distracting from them, and provide a classic yet elevated aesthetic for both entertaining and hosting intimate family meals. “With this collection, I am inviting you into my home,” Humm says. “The pieces reflect the same philosophy I bring to the kitchen every day: simplicity, intention, and a deep respect for craft. I wanted to reimagine the tools we use in the kitchen through the lens of design and purpose.”

As herbalist, author, and educator Rachelle Robinett sees it, we’re all herbalists—whether or not we know it yet. Her new book, Naturally: The Herbalist’s Guide to Health and Transformation (Penguin Life), offers an accessible, holistic introduction on how to weave herbs into our everyday lives, drawing on the deep, Indigenous-informed history of plant-based practices. From our gut health to our nervous system, from how we experience pleasure to how we rest, Robinett wants to equip people with the knowledge, curiosity, and practical resources to build their own personalized, long-term relationship to herbalism. As she writes in the book’s introduction, “The language of herbalism is shared among plants, between the botanical and animal, and with us, too, often subconsciously and biochemically. Physiologically, it imparts a vital verity that threads through all of us, and all of time.”

Here, Robinett, who also writes the Thinking, Naturally newsletter on Substack, shares why this relationship starts with listening more closely and reconnecting—to our bodies, to the natural world, and to the trees outside our window.

As someone who’s been studying, sharing, and working with herbs and plants for many years, what inspired you to publish a beginner-friendly, accessible guide to herbalism?

While the book is definitely accessible to anyone and everyone—beginners and experts—even if you’re a professional herbalist who’s been practicing for decades, I think we all appreciate reading colleagues’ works and learning from each other. So it’s definitely not only for beginners. But my mission with herbalism has always been to make it accessible. Common questions that I always receive are: How do I start? What is herbalism? Is it relatable to modern, even urban, lives? How does it fit into our world today? Is it scientifically valid? I took some of the most common questions and addressed them.

What kinds of resources did you feel were missing in the holistic health space that you hope Naturally will remedy?

We’ve been missing a guide that is both beginner-friendly and comprehensive. You can find plenty of books on herbalism, books that are “medicine-making” books—recipes and guides to creating tinctures or teas or any of these things you want to do at home. They don’t necessarily serve someone who doesn’t already know what herbs are, or what herbs they’re using. They might give a high-level introduction to certain herbs. You see a lot of herbal books that are kind of “A to Z”: These are herbs and the benefits of them. With Naturally, I worked very hard to achieve the vision that it would be a literary experience. In addition to being an introduction to this practice, I wanted people to learn the science and the art and see it in practice, and feel like they could start at zero, finish the book, and be completely set up with everything they need to begin with confidence, while also having enjoyed the experience and not having to read something equivalent to a textbook or an encyclopedia.

In addition to case studies, every chapter has a story from my private practice about the herbs in people’s lives. Then there are recipes, which are meant to be used as templates to be customized and personalized, and to give people a way of thinking that empowers them to practice this on their own, for themselves, for their loved ones. There’s also an herb-use table that includes all the herbs mentioned in the book and many more, plus how to use them in teas, tinctures, capsules, and powders.

You cover a lot of ground and explore the full range of how we can foster a relationship to herbal practices—everything from gut health with bitters to pleasure with aphrodisiacs, even psychedelics. Why did it feel important to look at herbs from all these different vantage points?

There are a few introductory chapters, then the rest follow categories of herbs that correspond to different body systems. I find that to be the easiest, best, most accurate and, again, most accessible way to learn herbalism, because there are thousands and thousands of herbs. The reality is that all of the herbal world is categorized based on herbal actions and how they affect us, and those generally correspond to body systems like the nervous system, the gut, the brain, the musculoskeletal system—the spirit, if you will, for psychedelics. When we start to look at categories, then all of a sudden we might be looking at a couple dozen plants total, you know? It simplifies the act of identifying the herbs that we need for the symptom we’re looking to treat, or the part of our lives we’re looking to improve dramatically.

I also pull back in every chapter and wax poetic or reflect philosophically on the concept we’re exploring. So, what is the nervous system doing? All of the time, it’s listening. How does listening relate to our health, and how might we learn to listen to our bodies better, and how might that change our lives?

How has deepening your understanding of the world of herbs and your relationship to nature helped you listen more closely to your body, to the world around you?

There are so many ways that herbalism asks and teaches us to listen. For example, when we’re wanting to treat something, it’s ideal to treat the cause and not just the symptom. The symptom is the loudest cue—the most acute. Often, allopathic medicine is just putting a Band-Aid on. What a lot of people come to plant-based medicine for is: What’s the herb for headaches? But you explore that deeper, and you try to identify the cause of your headache. Is it stress-related? Is it hormone-balance related? Is it related to a lack of sleep? Is it related to stiff joints or pinched nerve or muscle tension? That’s an act of listening more closely to our bodies, and herbalism asks us to do that, teaches us how to do that.

As I’m doing this interview with you, I keep gazing over here, because I can see this big tree outside my window. I think about how, once we cultivate a relationship with the natural world, we see it through herbalism in a different way. Yes, it’s medicine, but it’s also this ally that we can carry around with us in our pockets and our purses, and that gives us a better life. I think that teaches us how to, again, listen to ourselves, listen to the natural world in a deeper way. What might it teach us? What mystery, what magic, what science, what medicine might exist in that tree that I can see right now, or in that weed in my sidewalk or my backyard that, turns out, is also in that tincture that’s taking away my headaches?

Can you talk a bit about the roots of herbalism?

I like to say that we’re all herbalists, whether or not we know it. What is true is that in our pasts, there were herbalists, certainly, in all of our families. This used to be a way of life for everyone, and it still is a way of life for most of the world: living with plants and with nature, not only as medicine, but as a lifestyle of much deeper and more thorough integration. However, in the modern Western world, we’ve been separated from nature in that way for so many generations that for many generations now, herbalism seems new. There’s a lot of skepticism and distrust about it. I like to acknowledge that herbalism is not new. Much of modern medicine is developed out of herbs and plants. The vast majority of everything we know about herbalism now—that my teachers’ teachers’ teachers know—came from Indigenous use of these plants. Even further back, a lot of knowledge comes from Indigenous people observing animals using these plants. We stand on the shoulders of, if you will, all of the people all over the world who first identified the plants that we now use.

The book feels hopeful in that way. Even if we have become disconnected, it’s as if you’re saying, “Look, there’s a chance to come back.” As you wrote it, were there any everyday practices that helped you stay grounded and energized and connected to yourself?

Well [laughs], I would say the process was mildly traumatic. I have a tendency to work a lot, so writing it was very intense. It took me about eight or nine months. When my work becomes demanding or intense, my health practices become even more of a priority. Some of the practices that I employed were absolutely, positively daily exercise, usually prior to writing. I find that going for a really good run or a really long bike ride sets up my neurochemistry to be primed to access that sort of flow state and that pure focus when I’m writing, better than if I don’t move and I don’t move outdoors. I would also limit distractions completely, so I wouldn’t look at any incoming notifications from any device until after I was completely done writing every day. Often I would wake up, work out, sit, and write. And I would do sessions of one hour, with a ten-minute break in between, for about five to six hours.

And I use herbs all day long, every day. Along with my coffee, I take herbal supplements in the morning. I take herbs with my lunches. I use tinctures throughout the day, essential oils, incense. I essentially don’t drink alcohol, so I have herbal alternatives to alcohol when I want to relax. I use herbs for sleep.

I wanted to home in on something you shared in a previous interview with The Slowdown, where you offered your definition of well-being and wellness. At the time, you defined these terms as “a degree of contentment and peace with living in this body in this world in this way.” Has that definition from a couple of years ago evolved at all for you, or does it continue to ring true?

I love to hear my answer from some years ago. That does resonate. There’s an element that I would add to it. Well-being is essentially the sense or the knowledge that we are living the life that is right for us. I think that can manifest as contentment or peace. I think there’s also an element of pleasure, excitement, joy. So I would just add that high note.

To close, I was hoping you could share a few specific herb-based practices for the summer months, either that you practice yourself or recommend.

Iced tea comes to mind. But you know what’s so much more fun than iced tea? Tea popsicles. Or tea ice. Hibiscus is a good option—it could be literally any tea, though, and you make ice cubes out of it. It’s also a great way to make cocktails or mocktails that are not getting watered down, but they’re getting another layer in herbal infusion.

What else? I love using a lot of mints; they’re really aromatic, kind of cooling, mentholic plants. And I was just thinking of eucalyptus in the shower, being able to breathe in those plants while we’re taking a shower or a bath. Of course, dietarily, it’s nice to have more raw food. The farmers markets are incredible right now. That’s a really fun place to explore what herbs are mixed in with the culinary ingredients that might make their way into our food. It’s a beautiful way to work with herbalism that doesn’t require teas, tinctures, or anything else.

This interview was conducted by Olivia Aylmer. It has been condensed and edited. Interested in learning more about Robinett and her work? Read our prior conversations with her from 2022 and 2023, respectively, here and here.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

PIN-UP magazine’s founder, Felix Burrichter (see our 2021 “Media Diet” with him here), has a wide-ranging conversation with our editor-in-chief, Spencer Bailey, about his love for Isamu Noguchi, the constant specter of posterity, and crying in interviews. [PIN-UP]

Curated by art historian Glenn Adamson (the guest on Ep. 50 of Time Sensitive), the exhibition “Ground/work 2025” at the Clark Art Institute in the Berkshires (on view through Oct. 12, 2026) features outdoor installations by six craft-forward artists, including Yō Akiyama, Laura Ellen Bacon, and Hugh Hayden. [The Clark Art Institute]

Emergence Magazine’s podcast, hosted by Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, is featuring a special series this summer of audio practices exploring time. The first two delved into kinship and walking; this week’s is on Kairos, the Ancient Greek god of opportunity, who “expressed the possibility within a given moment.” [Emergence Magazine]

As the autonomous vehicle company Waymo has begun testing in New York City, Malcolm Gladwell (the guest on Ep. 125 of Time Sensitive) explains why he thinks driverless cars won’t work in urban settings. [Inc.]

The Slowdown’s senior editor, Olivia Aylmer, speaks with interdisciplinary artist Antonia Kuo about their photographic and sculptural works, “grounded in ecological, physical, and familial excavation.” [Flaunt]