In this week’s newsletter, we connect with the architect Kulapat Yantrasast on the new wing he designed for the Met, read Molly Jong-Fast’s heart-wrenching (but also hilarious) new memoir, pay a visit to the new V&A East Storehouse, and more.

Good morning!

There are few artists working today who so deeply engage the subject of time—or who make time such a central part of their work—as the Polish-born, Berlin-based Alicja Kwade, the guest on the latest episode of Time Sensitive. She could, in some sense, be considered a time whiz, a philosopher of time, or certainly an investigator of time. (For good reason, on the episode, I bring up another artist in this vein, Hiroshi Sugimoto, who was the guest on Ep. 114 last year.)

At its heart, Kwade’s work explores not only the slipperiness of time, but also the meaning of reflection, literally and figuratively. In so much of what she does, she contemplates the clock as a ruling device of our lives, but also as something that’s all mixed up, muddled, and impossible to pin down, and with her astute use of stone spheres, she also considers temporality from a deep time, metaphysical, and even cosmic perspective. Her art, time and again, leads viewers to pause and question their perception of reality. Harry Houdini is a hero of Kwade’s, and a certain sleight-of-hand magic does indeed show in her work. You think you may be looking at one thing, but actually, what she’s done is a sort of visual trick.

As the greatest art so often has the power to do, Kwade’s work leads viewers—and it has certainly had this effect on me, whether at Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Art, where her “Pars Pro Toto” (2018) is arranged in the garden, or at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where in 2019 she created “Parapivot” as that year’s rooftop installation—to look at the world, and time, in an entirely different way. For her latest exhibition, “Telos Tales,” currently on view at Pace Gallery in New York (through August 15), she has created a series of monumental steel-frame sculptures with treelike limbs alongside new mixed-media works that question the structures and systems—including, yes, time—that rule and shape our world.

Our conversation confirmed for me something I’ve long felt about the subject of time and, on further reflection, I think it’s why the terrain that we explore on Time Sensitive remains seemingly limitless. To talk about time is to embark on an endless investigation into reality, perception, art, science, and the meaning of life. Heady, I know. But I think you’ll get what I mean when you listen. As Kwade puts it, “We can never see the full picture of time. It’s completely impossible.”

—Spencer

“Time is the most abstract thing we have.”

Listen to Ep. 133 with Alicja Kwade at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

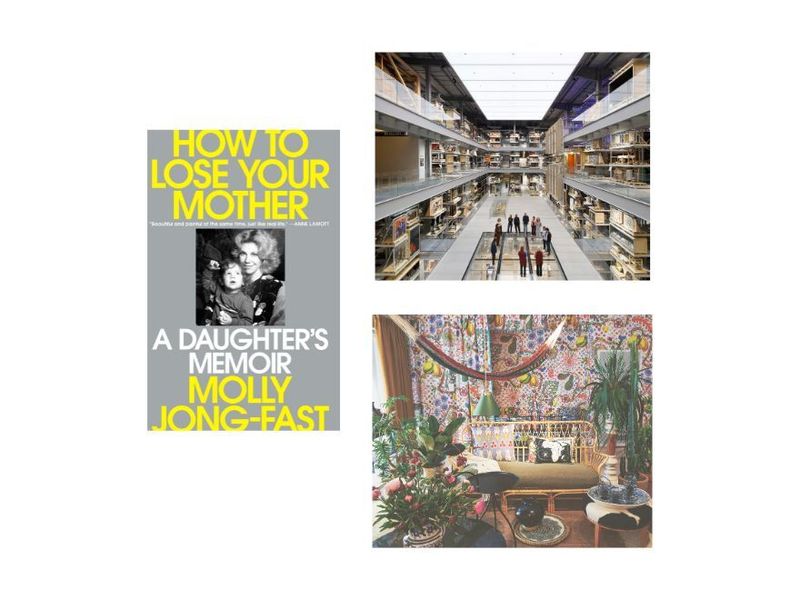

How to Lose Your Mother by Molly Jong-Fast

The latest book from the writer, political commentator, and podcast host Molly Jong-Fast, How to Lose Your Mother: A Daughter’s Memoir (Viking), is a searing, heartbreaking, and sometimes—thankfully, necessarily—hilarious text that lives up to its provocative title. (Stay tuned, by the way, for Ep. 134 of Time Sensitive with Jong-Fast, out June 18.) Jong-Fast’s mother is Erica Jong, the novelist, satirist, and poet best known for her 1973 novel Fear of Flying, and one of the leading voices of second-wave feminism. In How to Lose Your Mother, Jong-Fast tries to untangle a messy childhood—and even, to a certain extent, a messy adulthood—overshadowed by her narcissistic, once-famous, too often out-of-reach mother. It’s also a book about aging and frailty: In 2023, Erica was diagnosed with dementia, right around the same time that Jong-Fast’s husband learned he had a rare cancer. Like Joan Didion’s A Year of Magical Thinking, this is a book about an extremely difficult, gut-wrenching year. But it’s also much more than that. It’s also a book about coming to terms with things through humor, sobriety, grieving, therapy, writing, and time. More than anything, it’s a book about acceptance, or at least trying to find acceptance. “You don’t end your bad childhood simply because you want to,” Jong-Fast writes. “You don’t get to decide when any of it ends.”

V&A East Storehouse

Around a decade ago, when the Victoria & Albert Museum began planning an enhanced and expanded display, it could not have imagined a collection of this scale. The culmination of this effort is the gargantuan just-opened V&A East Storehouse in London’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Designing a vast cabinet of curiosities, lead architect Elizabeth Diller (the guest on Ep. 9 of Time Sensitive), of the New York–based firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, crafted a colossal four-story, 172,000-square-foot display comprising more than half a million pieces: 250,000 objects, 350,000 books, and 1,000 archival items. Revolutionizing public access to historical materials, the space combines the elegance and grandeur of a traditional museum showcase with the scale of an industrial warehouse, plus the pop-culture fun of getting up close to, say, a Givenchy silk taffeta scarf worn by Audrey Hepburn in the 1958 film Funny Face. With acrylic glass overlooking multipurpose conservation studios, the East Storehouse approaches art through the lens of transparency, transforming the relationship between museumgoer and archive, and offering a behind-the-scenes view into the V&A’s diverse holdings.

Svenskt Tenn: Interiors by Nina Stritzler-Levine

Documenting the legacy of the Swedish designer and entrepreneur Estrid Ericson (1894–1981) and the first century of the Stockholm interior design emporium she founded, Svenskt Tenn: Interiors (Phaidon) is no mere brand book. A colorful cultural history, this tome details how Svenskt Tenn redefined home furnishings and interiors in the 20th century—earning Ericson the title “Mistress of Modern”—and how the company continues to preserve craftsmanship today. Highlighting Ericson’s highly discerning eye; affinity for bold patterns (the Austrian-born architect, artist, and designer Josef Frank was famously a long-term Svenskt Tenn collaborator); and trademark designs, whether a 1930 coffee set or signature vases, this richly illustrated book by the design historian Nina Stritzler-Levine tracks Ericson’s enterprising evolution, one that forever cemented this stalwart Scandinavian institution on the international stage.

The Thai-born architect Kulapat Yantrasast—the founder of firm Why Architecture, which operates from offices in Los Angeles, New York, Paris, and Tokyo, and works with some of the world’s most storied cultural institutions—approaches his designs, rigorously executed as they are, with an open-armed sense of curiosity and playfulness. His latest project, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s newly redesigned Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, evokes exactly this. Housing collections from Africa, the ancient Americas, and Oceania, and featuring more than 1,800 works spanning hundreds of cultures, the space serves as a serene, sensitively crafted setting, its arched roof a finely-tuned cocoon. Yantrasast and his team have also led designs and renovations for museums such as the Grand Rapids Art Museum, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, and the American Museum of Natural History. Most recently, Why was tapped to create galleries for the Louvre’s new department dedicated to Byzantine and Eastern Orthodox Christian art. Here, Yantrasast reflects on the Rockefeller Wing and his earliest memories of the Met, speaking to us from his hotel room in Minneapolis ahead of a lecture he gave at the Walker Art Center this week.

When overhauling the new wing at the Met, what were the main elements you wanted to bring to the space that weren’t previously there?

This kind of project is meaningful to my team and me because of art and culture. They’re the reasons why we live. Culture and art are the main motivations to live longer. When I talk about culture, it’s not just art; it’s food, it’s music, it’s architecture, it’s all combined—the richness that humans have created. The Met is important in that sense. This is a collection of the Rockefellers, but it’s talking about Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. These three regions that compose seventy-five percent of the world are lumped into forty thousand square feet. When the [Rockefeller wing] first opened in 1982, it really made the Met encyclopedic, because up until then only twenty-five percent of the world was represented. It took a long time for Western museums to realize that other cultures also make art. I was lucky enough that I came across art from other cultures when I was 7 years old, when my parents first took me to the Louvre. I was struck by the discovery that there are works that do not look like what I grew up with. I hope that what I create at the Met or at the Louvre is not just for New Yorkers or Parisians, and that it creates a sense of empathy in the same way that perhaps if you go to a Chinese restaurant or Vietnamese restaurant, you better understand the people behind it.

What was your team’s process at the Met? Can you walk me through the different steps—working with the curators and the museum’s staff—down to the actual design and build?

We started by [having] workshops where we listened to the curators, to the conservation team, to understand what the priorities are and what success looks like. Within each region—Africa, Oceania, and the Americas—there are hundreds of cultures that have nothing to do with each other. So some of them might not even like each other. But they get lumped together in this mix. So we need to respect, first of all, the region, and then within each of the regions, the distinctions between them. Big museums only show a small percentage of their collection, because they don’t have space, so we designed a casework to make it easy for them to use and change so that the objects can rotate. Conservation is a big part of this because many of the objects need to be conserved. We did around two years of very intense design. Then the pandemic happened, and then, on top of that, we had fundraising. The Met was not trying to rush, and there was a lot of maneuvering, because we needed to be able to do construction while also allowing the public to go through the museum, and minimizing disruption. Everything was done with a level of love. This is not an exhibition that will go on for three months. This is going to be a lifetime.

What did you learn while working with this collection of Indigenous and ancient artifacts? Did your understanding of those objects shape the space?

I think we don’t want it to be something that’s too framed. When I work on a project like this, I feel like I get multiple Ph.D.s at the same time, because the curators and conservators see us as partners. What we’re trying to do within each of the regions is ask, “What are the right architectural references to give a sense of place?” The materials for the Oceania section actually have a little bit of sand. If you look closely, it reflects the light differently, so it has this beautiful subtle color. The Africa section has a very pale white-yellow color. In the beginning, we talked about using wood as a way of creating the background, because most of the objects use wood, but wood on wood sometimes doesn’t really work, so we changed the idea and picked a very neutral but soulful color to carry the section. In the American section, the space is created as a courtyard, almost like the pyramids and the Zócalo. We used limestone, which is very common in ancient America and has a cream color that works well with the collection.

In our fractured, time-splintered age, how can we rethink the role of the museum?

One thing that’s important is we have open spaces with benches where visitors can sit and look at the objects. If you spend time sitting looking at an object with concentration, your blood pressure comes down. The wing itself is forty thousand square feet, so we literally have a two-hundred-foot-long window. Along the park, we have many benches and seating areas where people can come and sit down, and look at the park and see the art at the same time, which I feel was so needed. Up to now, that has been blocked and not used, because the light came behind the objects, so we redesigned all the windows. With this new technology, we’re able to filter and soften the light that comes through, and it doesn’t harm the art. In almost every crisis, people take refuge in art and nature, and I think that we can really provide a good refuge there. A lot of the art in this wing is very spiritual, connected to ceremonies and rituals. Even if you do not belong to a ritual, you can imagine the power and the meaning within it.

What are some of your earliest memories of the Met?

I didn’t come to America until I was 21 years old. I was doing summer school at Columbia University, and it was one of the best summers of my life. I’d go through the Met almost every day on the way to work. When I went for the first time, the Temple [of Dendur] made me feel so intimidated, like, oh wow, I cannot do anything embarrassing. I have to not make noise. I have to behave myself. What struck me was the grandeur and the objects themselves. It led me to think, Wow, humans made these. That made me want to become an architect. I felt that I wanted to be able to create something beautiful and inspiring for other people in the future, so that they can look back and say, “People actually made this.”

This interview was conducted by Dalya Benor. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

Writer Spencer Kornhaber speaks with several thinkers arguing that America has been sapped of its creative energy—and he still finds the potential for optimism in what often feels like an unoriginal haze of content [The Atlantic]

The Venice Biennale announced that it will move forward with the late curator Koyo Kouoh’s vision for its 61st edition, themed “In Minor Keys” and conceived within the curatorial framework that Kouoh was developing in her final months [Artnews]

Landscape designer Walter Hood (the guest on Ep. 103 of Time Sensitive) wants to “unwind racial planning, break down segregation, and align design with social justice” by repairing public access to Manhattan’s Lincoln Center—with the visionary architects Michael Manfredi and Marion Weiss adding a 2,000-seat outdoor music pavilion [Curbed]

Art critic Holland Cotter hails the Met’s new Michael C. Rockefeller Wing as “wondrous,” describing the art on view as “dizzying in its inventive range” [The New York Times]

Following its recent renovation and restoration by the architect Annabelle Selldorf (the guest on Ep. 104 of Time Sensitive), the Frick Collection will open its first restaurant in 89 years this week [Eater]