In this week’s newsletter, we talk with Alexandre de Betak about “peri-disciplinarity,” review Keith McNally’s rollicking yet heartbreaking new memoir, contemplate Jia Tolentino’s time-splintered view of reality, and more.

Good morning!

I’d like to begin this week’s newsletter by saying what a special, full-circle moment our latest episode of Time Sensitive—featuring the drummer, percussionist, and composer Billy Martin—is for me. In some sense, this conversation has been 27 years in the making.

Many of you may recognize Billy’s name from our end credits—he created the Time Sensitive theme song—and others of you may know him as the drummer in Medeski Martin & Wood, a trio that for 30-plus years now has been making experimental, uncategorizable, instrumental jazz-funk-groove music that is wholly, definitively, expansively their own. I’ve been a drummer myself for more than 25 years now, and have been listening to MMW’s music since 1998, when, at age 13, I picked up their album Combustication at a Blockbuster Music store in Denver. Around a decade ago, a girlfriend of mine at the time surprise-introduced me to Billy by inviting him over for a birthday dinner at my home. He and I have been friends ever since.

What impresses me so much about Billy, even beyond just his drumming, is his outlook on work, life, and creativity. Billy’s improvisational attitude shows up in all that he does. He is also a builder—he constructed both a Japanese-style teahouse and a music studio in his backyard in Englewood, New Jersey, and over the past year has started making percussion instruments out of bamboo—and with a great sense of rigor and structure yet free-form openness, he approaches his drumming and composition work almost as an architect, exploring sound in a metaphorical room-by-room way, eventually resulting in what could be considered a “house.” Billy’s drumming is a beautiful thing to behold.

This open perspective connects, in a fascinating way, to our latest “Interview With,” below, with the French producer, designer, and artist Alexandre de Betak. In the conversation, conducted by our new contributing editor Dalya Benor, de Betak speaks about his deep belief in “peri-disciplinarity” and mentions how, for his latest project—a pop-up dinner series with the culinary outfit We Are Ona—he sought to create a “synchronicity between sound and the space and the light.” It’s a statement that reminded me of Billy’s notion of “rhythmic harmony,” and that also aligns with so much of what I spoke about with the theater director Robert Wilson, back on Ep. 96 in 2023.

Harmony, I think that’s what we’re all after, in one way or another.

—Spencer

“When you make a sound, put your heart into it. Even when you’re alone, I think you have an audience.”

Listen to Ep. 131 with Billy Martin at timesensitive.fm or wherever you get your podcasts

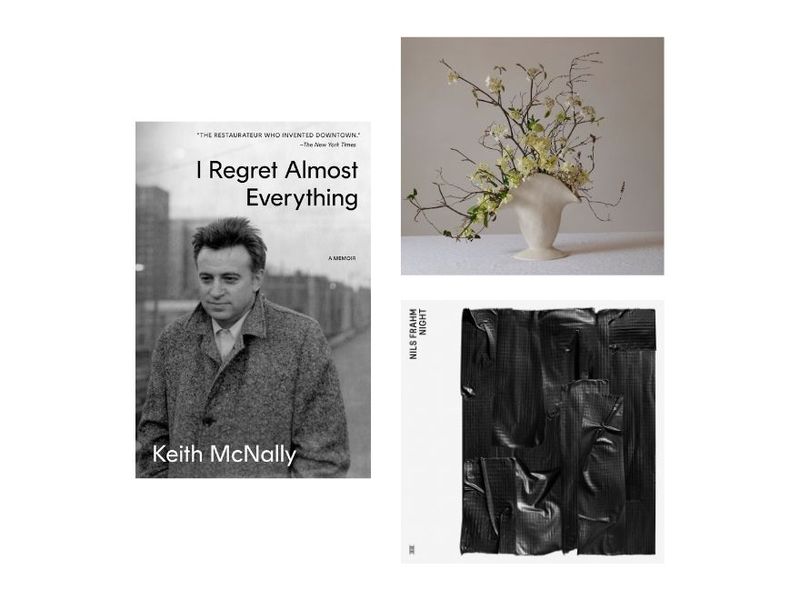

I Regret Almost Everything (Gallery Books) by Keith McNally

This memoir’s provocative title suggests a text that is rollicking, entertaining, and as downright delicious as a late-night steak frites at Balthazar, the stalwart French brasserie in New York’s SoHo neighborhood owned and operated by the book’s author. Indeed, Keith McNally’s I Regret Almost Everything is exactly that—and then some. With his pristine, precisely worded prose, McNally proves himself to be an achingly self-aware memoirist and an exquisite sentence-maker. His deep interest in words is evident throughout the book’s taut, well-honed paragraphs. Beginning with an August 2018 suicide attempt, which followed a 2016 stroke that left him partially paralyzed, McNally unpacks his life, rich and colorful as it has been, through a heartbreaking lens. But that is not to say I Regret Almost Everything is a sob story. Quite to the contrary. McNally is often dryly, pugnaciously hilarious, and sometimes, as he often is on his Instagram, even cutting. From his working-class upbringing in the East End of London; to building and running the Tribeca restaurant Odeon in the ’80s alongside his then wife, Lynn Wagenknecht; to his failed attempts at becoming a filmmaker; from his many successful restaurants (Balthazar, Pastis, and Minetta Tavern, to name a few) to those that were less so (Cherche Midi, Augustine), this book oozes insight, wisdom, and Jenny Holzer–level truisms (“Magnificent views don’t necessarily prompt magnificent thoughts”; “The brink of change is always more thrilling than the change itself”; “One of life’s cruelties is that we only recognize special times in hindsight”). “Humor and integrity are two qualities I value above all others,” McNally writes. This memoir shines with both.

Spade Vessels by Simone Bodmer-Turner

With her new Spade vessels—her first family of vases in five years—the artist, designer, and ceramicist Simone Bodmer-Turner introduces a new chapter in her ever-evolving creative practice. Comprising three small, medium, and large sculptural forms—Più Spade, Spade, and Tall Spade—the series marks Bodmer-Turner’s return to pottery following forays into both furniture, with the “Take Part In” exhibition at Matter Projects in 2022, and lighting, with her “A Year Without a Kiln” exhibition at Emma Scully Gallery in 2023. Created using porcelain and sealed with a warm white glaze matte finish, these wide-mouthed vessels evoke the wondrous, wildflower- and high grass–lined landscapes surrounding her Massachusetts studio in the Berkshires. Her intention, Bodmer-Turner tells us, was to create ample space for flowers to sing—to guide their stems outward, almost as if they’re a part of the vessels themselves.

Night by Nils Frahm

With his latest studio album, Night, the Berlin-based composer and pianist Nils Frahm returns to the signature, contemplative, piano-centric harmonies that marked his early-career releases The Bells (2009), Felt (2011), and Screws (2012). As a companion piece to his 2024 album, Day, his latest work feels less like a sequel and more like an internal interrogation of the performer’s emotional center: five measured, slow-to-unfurl compositions performed on a custom-built Klavins M450 piano installed at his studio at the Berlin Funkhaus complex. Frahm’s careful juxtaposition of sound and silence is on full display in Night, evident from the opening piece, “Wesen,” which unfolds with menacingly slow accuracy, all the way through to “Kanten,” a minimalist piano performance that plays out entirely on his piano’s lower keys. Its middle tracks—“Monuments Again,” which teases a rich, flirty, jazzlike sound, and “Listening Over,” an eight-minute long sermon—add complexity and depth to the otherwise rhythmic cadence of the other songs. The final tune, “Canton”—ironically, the album’s debut single—is perhaps Frahm at his most melodic and tender, a gentle reminder of the emotional tenor he brings to each performance.

In a career spanning more than 30 years, the producer, designer, and artist Alexandre de Betak has produced around 1,500 fashion shows—conceptualizing stage design, lighting, and scenography for brands such as Dior, Louis Vuitton, Burberry, Jacquemus, and Rodarte, among others. For his latest collaboration, de Betak partnered with the Paris-based culinary events studio We Are Ona—founded by the sommelier Luca Pronzato—to create an immersive, weeklong pop-up dinner series that first launched in Paris and landed in New York during the Frieze Art Fair. Applying his installation and lighting compositional mastery to a colossal, empty office space on the 41st floor of the WSA office building in New York’s downtown Financial District, de Betak transformed its bare, concrete floors and skyline views—with the help of more than 100 feet of overhead lighting and swivel chairs—into a dinner theater stage he describes as “simple yet radical.”

Here, from the spare, Kubrickian setting that featured a tasting menu arranged by the Paris-based chef Sho Miyashita with sake by Heavensake, de Betak speaks with us about the project and his desire that guests leave dinner feeling as if they’d been in a movie.

How did you get involved with We Are Ona? What was your process for conceptualizing the design of the New York dinner?

I met with Luca quite a few years ago. I often told him we should do something together. I recently decided to let go of doing fashion shows and focus on my art and my light installations and sculptures. He convinced me and said, “Let’s do a trilogy together.” The first part was in Paris in December, and then Hong Kong for Art Basel, and this is the last one, in New York for Frieze.

I decided to do an office-inspired light sculpture. It’s essentially one long light sculpture that becomes a table for a week, and after that, we will turn it into a series of sculptural objects. The idea is a bit the same in all three, but very different in a way. To do a sculptural, quite minimal line of light—there’s something very simple and quite radical—it seems like it would be very cold, but hopefully you realize it’s not. The light is very warm—it’s very strong, but it’s very flattering as well.

How does it feel to be making your own work now as an artist and designer?

It’s interestingly not very different. What changes is the purpose, not so much the craft. I’ve always designed important installations, but they always had the purpose of highlighting something else. Now, I decided that they can highlight themselves.

You once said that your approach is “the marriage of what we call the ‘cueing’ of space and time, of music and light; the synchronization of all the elements.” Can you speak to your philosophy and how you implemented it for this project?

I implemented [that philosophy] most of my life doing [fashion] shows. It’s hard to explain where it comes from. What touches you the most is a combination of elements, and in my case the elements that touch me the most—the synchronicity between sound and the space and the light—make memory and feelings much more important. This [installation] is more minimally radical, so there is no “cueing.” I designed the bulbs with different light temperatures so that they can adapt to the hours of the day. I like music to be music. It’s either there or it’s not.

You also said in that same interview, “If we all give ourselves the time and the distance, we can reflect on things that no one has made the time or space to think about before.” What are you thinking about currently? How are you slowing down?

For both artistic and political reasons, I am more drawn towards perennial scenes versus ephemeral. I love ephemeral moments—I think life is a collection of ephemeral moments that hopefully we remember. It’s about time to take more time to do them and to do things that will really last. Even if it’s semi-ephemeral, what I’ve done with We Are Ona, in reality, it will evolve into pieces that remain. That’s something that’s really important for now, so I am lucky that I can slow down in the sense that I don’t do a [fashion] show every other day.

I like the adrenaline and a short deadline, but I also believe that it’s important to dig deeper into any form of creation or idea that I have, and “waste time” and go deeper, creatively and artistically. I’m also enjoying the fact of perenniality and quality.

What draws you to food and how do you think about it as a medium? What do you like to cook?

I love food, I love cooking. I love life, I love good times. So it was very natural for me when Luca asked me to conceive a few of these together. I love to make pasta. They call me Pasta Papa. [Laughs] I like cooking for other people. I make pastas for two hundred people. I’m used to scale—I like scale. [Laughs]

How does it feel to have your name at the forefront—versus being behind the scenes—and working with other brands to bring their experiences to life?

It feels very natural. The context is different and the purpose is different, but what I do in itself is the same. I’ve always created and designed.

You sold your production company, Bureau Betak, to The Independents Group in 2021, where you now serve as chairman. What’s your vision for the role?

I’m the creative chairman for the group. I’m very happy that we launched a program called L’Incubateur, which is an incubation program for young talents around the world, in similar or complementary fields to the ones that the group already has—such as designing and producing events, communications, advertising, PR, A.I., tech in general, or sustainability. We’ll do an announcement of the first selection very soon. I’m enjoying the creative and strategic thinking that I can contribute.

What other areas of design do you want to go into?

I’m designing a few houses. They’re treated like architectural, artistic installations more than houses. I enjoy removing the goals of practicality from my life. This is the artistic freedom that I really needed. I’ve always believed in peri-disciplinarity—it’s a time when creation is important, when innovation is important, when a free spirit is important.

This interview was conducted by Dalya Benor. It has been condensed and edited.

Our handpicked guide to culture across the internet.

The late South African art curator Koyo Kouoh—who was set to be the first African woman to lead the Venice Biennale as artistic director in 2026 and helped revolutionize the presence of African art on the global stage—is warmly remembered by Thomas Girst [Artnet]

Viet Thanh Nguyen, the author of the new book To Save and to Destroy: Writing as an Other (and the guest on Ep. 112 of Time Sensitive) reflects on loss and resilience 50 years after the fall of Saigon [Harper’s Bazaar]

Jia Tolentino contemplates “whatever strange thing is currently happening with time,” noting how “the past has vanished, the future is inconceivable, and my eyes are clamped open to view the endlessly resupplied now” [The New Yorker]

The MacArthur fellow and poet Ocean Vuong recalls his adolescent struggle to find a sense of belonging and the unexpected turning point that sparked a rise of self-reflection in him [The New York Times Magazine]

Mixed-media artist William Kentridge goes behind-the-scenes of his in-studio craftsmanship with his latest book, Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot [Hauser & Wirth]