A Walking Tour of Greenwich Village With Architecture Critic Michael Kimmelman

It’s a late afternoon in early November, nearing dusk, and I’m sitting with Michael Kimmelman, the New York Times architecture critic, inside the West Village outpost of Daily Provisions, a café from the New York City restaurateur Danny Meyer. A sort of contemporary town square, Daily Provisions is exactly the kind of place that Kimmelman, who’s widely known for his egalitarian, public-oriented prose, would consider from a development and urban design perspective: its impacts on the streetscape and the neighborhood, the community around it, and the city beyond. (In 2016, he wrote about another Meyer establishment, Union Square Cafe, unpacking the implications of the then-new location and layout of the legacy Manhattan restaurant.)

Located on the corner of Downing and Bedford Streets, Daily Provisions also happens to be a block from the red-brick prewar apartment building Kimmelman was raised in, at 10 Downing Street, along Sixth Avenue. This is the neighborhood of his youth, but this being New York City, and Kimmelman (aside from his studies at Yale and Harvard, from 1976 to 1982; stints in Philadelphia and Atlanta; and a period in Berlin, from 2007 to mid-2011, during which he was the Times’s “Abroad” columnist) being a lifelong New Yorker, the Village remains his neighborhood, even if he technically now resides on the Upper West Side.

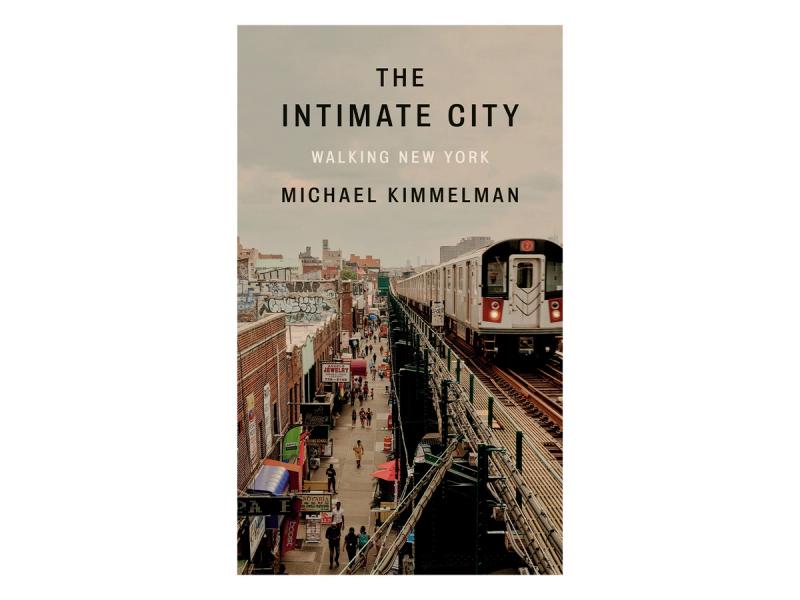

I’m meeting Kimmelman here to discuss his new book, The Intimate City: Walking New York, but also—playing directly off of its theme—to take a walk. Before we head out, we first talk about the book over cappuccinos.

Comprising 17 deftly, expertly composed walks with architects, urban planners, writers, and others, The Intimate City provides multilayered views of the city through the lenses of Kimmelman and such visionary thinkers as the writer Suketu Mehta, the architects Marion Weiss and Michael Manfredi, and the landscape architect and urban designer Kate Orff. Conceived at the beginning of the Covid-19 lockdown and originally published in the Times—beginning with a walkthrough of an empty Times Square with the architect and designer David Rockwell, renowned for his Broadway sets—the project is at once a time capsule, a memorial, and a paean to this city that more than eight million people call home. When I ask Kimmelman about his March 2020 walk with Rockwell in particular, he says, “There was something terrifying about the emptiness. I remember feeling like we had the city to ourselves, which was this great gift and also like, Oh, my God, if anyone comes near us, we’re going to die.”

In a similar vein to his 1998 book Portraits: Talking with Artists at the Met, the Modern, the Louvre, and Elsewhere, for which he walked through those institutions with artists including Balthus, Cindy Sherman, and Kiki Smith, The Intimate City explores certain neighborhoods themselves, from Harlem to Midtown Manhattan to Jackson Heights, each effectively as its own sort of gesamtkunstwerk.

An “abiding mission for the project,” Kimmelman tells me, was to give readers “a sense of distraction and hope.” For him, the series was also, in many ways, about taking a prolonged period of slowdown to patiently probe and prod the city and many of its multifarious layers. “If you just look at the city as a bunch of buildings,” he says, “you’re not really understanding what made it and what can change it, and how we live it.” A sort of close reading of the vast, combustible metropolis that is New York, The Intimate City offers an alternative way of seeing, being in, and feeling the city: lost in its wonderment, with a critic’s openness, curiosity, and candor, and guided by some of its shrewdest urban-design minds—all in the midst of a pandemic.

I ask Kimmelman how he went about organizing the walks, which have a breezy, easy-to-read quality, but are also highly intelligent and densely packed with detail. Noting that the strolls were “the product of a lot of work,” Kimmelman says, “Even a great jazz musician—I’m not conflating myself with that; I’m merely making that point about jazz—does have a lot of preparation beforehand. All of the people I talked to took this seriously. Nobody was winging it here. I wasn’t, either, and that was important. That doesn’t mean that the conversations weren’t also spontaneous and real, but we were trying to create a tone and a kind of intimacy representative of how you would walk around the city with a friend. Each walk also contains within it an enormous amount of obscure, complex information.”

Cappuccinos done, Kimmelman begins our tour. Admittedly, we sort of wing it—I told him to take me wherever strikes him, without much foresight or planning. Not that this is a particularly challenging assignment for him: These streets are his home turf, and a literal walk down memory lane. What follows is our brisk hour-long ramble through the neighborhood, condensed and edited for clarity, beginning at 10 Downing Street; continuing on to Winston Churchill Square, up Minetta Street, and down Minetta Lane and MacDougal Street; back up to Washington Square Park; over to the gated Jefferson Market Garden; and finally, with a stop at Greenwich Avenue and Charles Street, next to his alma mater, P.S. 41.

Here, Greenwich Village through Kimmelman’s eyes.

DOWNING STREET AND SIXTH AVENUE

Spencer Bailey: I didn’t know until reading your book that Sixth Avenue used to be what you call an “eight-lane Thunderdome.” This is where the other two lanes were [points to the widened brick sidewalk]?

Michael Kimmelman: Actually, it’s hard to remember from my childhood. The sidewalk was widened in order to narrow the street, because we had just this crazy amount of traffic, and it would get clogged here. I don’t want to mislead you, but fundamentally, there were, I think, two more lanes—six there and two more here.

10 DOWNING STREET

Kimmelman: My dad’s medical practice was on the ground floor. Now, you have to understand, Spencer, this does not even vaguely resemble what this building looked like. It was an incredibly banal, kind of dumpy building. It was horrible and rat-infested.

You see that person in that window [points to a window on the second floor, above Clover Grocery and the restaurant Hancock St.]? That was my bedroom. And that was my fire escape. My piano was in the den that’s straight ahead. This was my parents’ room here; that was my parents’ bathroom. We had one of the building’s most extravagant apartments, which as you can see is extremely straightforward.

It was quite noisy here. I would look out on the traffic, and also on the park, where I would go and play basketball and occasionally throw a baseball with my dad.

I went back into that apartment a few years ago and discovered that it was split in two and that the rent on each was—I don’t even want to tell you, but let’s just say, an incredibly mediocre apartment, in an incredibly loud place [Editor’s note: As if on cue, two fire trucks came screaming up Sixth Avenue as Kimmelman said this, with their horns and sirens at full blast], in a not-remarkable building, between the two, the monthly cost was twice my college tuition as a freshman. Which tells you what happened to the Village, that such a place would change this much.

Downing [Street], where we just walked, one reason I wanted to meet you there was because there were a couple of artists, friends of the family who had bought a place there, but fundamentally, it was a back alley, mob run, with a few garages and lots of nefarious things going on. It was a place you really wanted to avoid.

WINSTON CHURCHILL SQUARE

Kimmelman: I used to go to this little playground as a kid. Before this area here, which has now been turned into a garden, was greened, it looked like a little penitentiary for toddlers. It had that feel to it. So you’d go onto this ratty alley and into your children’s prison to swing on the swing over a concrete floor.

MINETTA STREET

Bailey: From your walk through the Village with the architectural historian Andrew Dolkart, it was interesting to learn about the neighborhood’s mob history, and how at one point the gay community and the mob were quite linked.

Kimmelman: Absolutely. Well, the mob had—listen, I don’t want to associate the Italian community here simply with the mob. This was a very Italian neighborhood and there was also the mob. But that was true. The mob made gay bars possible because New York City didn’t.

Bailey: Right. The mob would pay off the cops or whatever.

Kimmelman: That’s why there was a Stonewall [Inn], even though it was a dump. But you see that change after Stonewall, and then places like Crazy Nanny’s, which took over these odd little triangles that were created by the changing streets, after Sixth Avenue cut through the Village.

By the way, the Minettas [Minetta Street and Minetta Lane] are interesting. This is one of the things you don’t think about until you’re told, but why does this weird street curve off this way and deadend? And then another Minetta [Minetta Lane] is over there [points north, to Minetta Lane]. Well, this was a creek. It was a waterway, and it curved around here and then drained basically toward Downing. Originally, this was an area where freed African American slaves lived. So the Village—here, and if you go up the Minettas toward Washington Square Park, that southern end of the park—was an African American neighborhood. Then immigrants started to arrive, especially from Germany and Italy, and they began to take over that part of the neighborhood.

You know, so much of the history of New York is the constant dislocation of African Americans. That’s the story at Penn Station, for instance. The Tenderloin, which was a largely Black neighborhood, was cleared out. And where did they go? They went to the next place that was possible, some of them having come from here, and that was Harlem. So Harlem’s development, if you track it back, runs through Minetta Lane.

MINETTA STREET–MINETTA LANE INTERSECTION

Kimmelman: All I’m going to tell you here is, since I’ve written about bikes… I always walked home from school. Even as a little boy, in second, third grade. And then I started to ride my bike home from school. It didn’t look all that different, this street.

But I would swing down here, coming from Friends Seminary—I went to P.S. 41, and then to Friends, with a short stint [in between] at I.S. 70. One day, I came down the street, speeding, and there was a giant pothole, more or less right here [points at the street corner, just beyond a stop sign]. And I couldn’t quite see the turn. So my bike went into it, stopped dead.

Bailey: Did you go flying?

Kimmelman: I went into the wall—splat, like in a cartoon—and slid down it. All I remember is that one of the elderly Italian women in the neighborhood, who was, I think, a patient of my father’s, came from the corner over there, which was then a Pioneer Supermarket, carrying the Pioneer bags, stepping over my body as she went to her apartment. I thought, That just tells you so much about New York. She sort of knew who I was. She was like, “He’s alive, he’s fine.” That stopped me from riding the bike for a little while. But every time I come to this corner I relive my near-death experience.

Bailey: Against that very brick wall.

Kimmelman: Yeah, it’s got my head mark on it.

MINETTA TAVERN

Kimmelman: We’ve been walking through what are fundamentally a bunch of alleys—Downing Street, the Minettas. Now, because the economy has changed and the nature of the Village has changed, we’re at Minetta Tavern, at the corner of MacDougal [Street]. Minetta, when I was growing up, was one of the better, not the best, Italian restaurants. This area was full of these places. Now, of course, Minetta Tavern is super high-end and quite good.

Bailey: And with a bouncer at the door.

Kimmelman: And with a bouncer at the door, yes. But look at these buildings. There are a lot of tenement buildings. You walk down MacDougal and you think, Okay, it has always been this sort of thing. On some level, that’s true. But it’s quite distinct architecturally from where we’re going to walk in a second, and that’s because this area, when tenements started to be built, the cold water flats, the Village was full of these places. That’s what made it attractive to immigrants and to what became a bohemian community. Because it wasn’t what we all have an image of now, which are these higher-end townhouses.

When people walk through the Village, or a neighborhood like this, they don’t really see why things are where they are. The southern end of Washington Square Park was one economic class, and the northern end was the other. That’s important. Because the Village was maybe the first place in the city where you had within a single neighborhood these very distinct lines drawn between classes. You could begin to read the city as a map of privilege, poverty, different kinds of economic opportunity, races, and so forth.

MACDOUGAL STREET (BETWEEN BLEECKER AND HOUSTON STREETS)

Kimmelman: These buildings were built as a different model that was turned inward and created this [interior] garden. I would come here to visit my aunt and uncle. This is a good example of the way in which the Village was a really peculiar neighborhood. My aunt and uncle lived here, and Bob Dylan lived next door.

This was built for middle-class clientele. It’s a beautiful model of urban living, in which you sort of are on the street, but you also have a shared space in the back. A lot of the Village developed housing in the back, so there are a lot of townhouses, brownstones, other buildings—like on Jones Street, where I used to go visit friends—where you go in and don’t see it, but the backyard is essentially a shared garden.

For instance—this was a typical Village situation—I used to go to my friends on Jones Street, play basketball in the backyard. It was a cobblestone yard with a tiny house in it. Those houses were built, many of them, because you had a growing working population, and they needed extra housing. It wasn’t what it now sounds like, which is a beautiful little house with a cobblestoned, tree-lined garden in the Village. It was: We’ll just build a house here because somebody needs a place to live.

By the way, the famous photo of Dylan walking down a street—he’s on Jones Street, on that [The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan] album cover.

WASHINGTON SQUARE PARK

Kimmelman: The northern part of the park became a place where the wealthy settled as they moved out of Lower Manhattan. They moved out of Lower Manhattan because it was overcrowded, and there was a lot of disease, cholera, and so forth. They wanted to move essentially to the country, and in the early days of the city’s development, this was the country. This had been a parade ground, and also a cemetery, and then it became a park. As a result, it was a sort of open space. Wealthier, old, blue-blood families would move to the northern parts of the park. Around them, lower Fifth Avenue developed.

It’s interesting how you move from one [part of the Village] to the other. And what has happened? We moved from the overcrowded sidewalks, noise, density, a certain amount of light, to something that feels like we could be in London, in a gated park. The beauty of New York is that you do this without noticing. You move through these extremely different spaces that are somehow seamless and therefore feel like they’re the same neighborhood.

WASHINGTON SQUARE NORTH (BETWEEN FIFTH AVENUE AND MACDOUGAL STREET)

Kimmelman: I’m stopping here because my friend—it’s a horrible real estate story. I had a friend who grew up in this building here, a floor-through to the back—in this case, to the mews. When his mother died, at over the age of 100, my friend was deciding what to do, because the landlord who was here, who had known this woman for fifty years, said to my friend, “Look, you can keep the apartment. I would never want to kick you out.” But he had moved to Portland, Oregon, and didn’t think he wanted it. I said to him, “Well, you don’t want to pay for an apartment when you’re not living here.” He said, “It’s not really the money. She told me I’d pay the same rent.” I asked, “What is it?” He said it was $112 a month. So this apartment facing Washington Square Park was $112 a month, and he gave it up. I wanted to kill him.

So why was the rent $112 a month? Well, it turns out that the story of these buildings is a little more complicated. Because, while the landlord owns the building, there’s some dispute about whether she really has the right now to control the building. Why? Because the descendants of the Dutch family that originally owned all of this land when it was a farm still own the land under these houses, and therefore believe that they have some claim to ownership of the buildings themselves. Because, of course, now the buildings are worth something. N.Y.U. took over all the rest of these [points to the buildings to the east, one of them with a purple N.Y.U. flag hanging at its entrance], but these particular buildings on the western end of this row remain privately owned.

I think the landlord felt they weren’t going to start to change things around and start raising red flags about this, because there’s still some dispute. The pre-colonial farming Dutch family—now a foundation in, I don’t know, Amsterdam, The Hague—has decided that this property is worth something. So right here you have the entire history of New York City, from the Dutch; to the first families, like Henry James, who came here; to my friend living here for all those years; and now, the Dutch again.

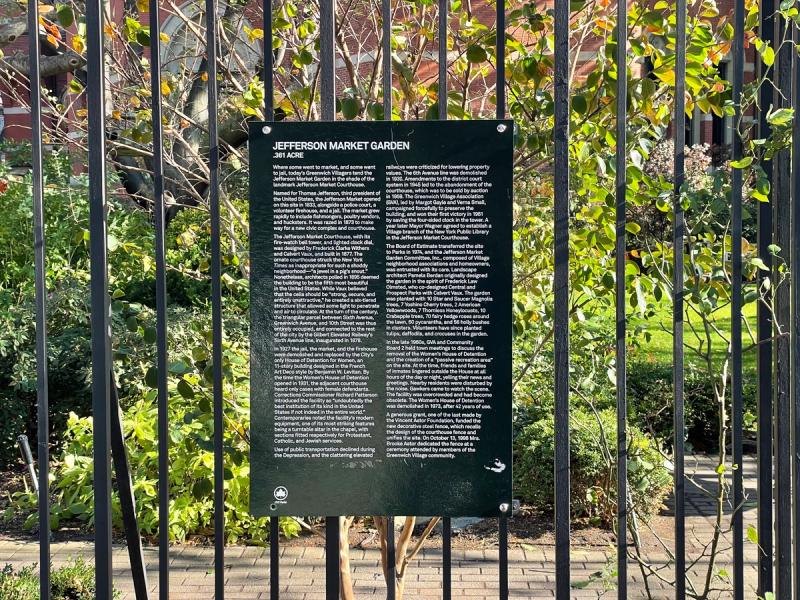

JEFFERSON MARKET GARDEN

Kimmelman: We’re now at the Jefferson Market Garden, which was the site of a women’s house of detention. That incredible, weird Victorian building, which is now a library, was a courthouse.

One of the city’s most beautiful, although not always accessible, community gardens is in some ways a memorial for the suffering that many women were put through in this particular site. When I walked home, I would walk past—this was a jail. Women were kept here, and many of them, it turns out, were abused. And they would be screaming out the window, constantly.

Just imagine, this was actually a place where you were walking past a twenty-four-hour site of suffering and misery. But what was the history of the women’s house of detention? Why was it here? It’s because the jail system in the city was so abusive and broken that the city decided, at a certain point, that it needed to build “reform” jails, and that they should be in neighborhoods like this. So placing a women’s jail in the Village, next to the courthouse, was considered a more humane thing to do. And not only that, but the jail itself was to be a humane place. So it was an Art Deco building, if I recall, with art in it. The idea was that it would be a place of culture, a place of architectural distinction, and in the beginning [when it opened in 1931] I suppose that’s what it was. But like so many of these experiments in the city, it was an abject failure.

As a result, the city decided it needed to reform its jail system and build a place that would provide a campus for women, as well as for men, someplace that wasn’t smack in the middle of things, but was a refuge, and would have a whole new regime of progressive incarceration. The way to do that was to move to a place called Rikers Island, because Rikers would be so much more humane and better-run than this urban disaster, which had grown out of a failed urban-reform movement.

Bailey: So this little piece of greenery can be tied directly to Rikers?

Kimmelman: Yes, and Rikers is now doing what? Undergoing the same transformation, to come back to neighborhoods where people will be embedded back in the city, and will have a much more reformed system. So we’ve been through this cycle before.

For me, it was just a very, let’s say, formative experience, to come home from P.S. 41, right here around the corner. And while deciding if I could afford to get a cupcake at Sutter’s bakery, I would also be yelled at by these women who were trying to describe the horrors of what was going on inside there.

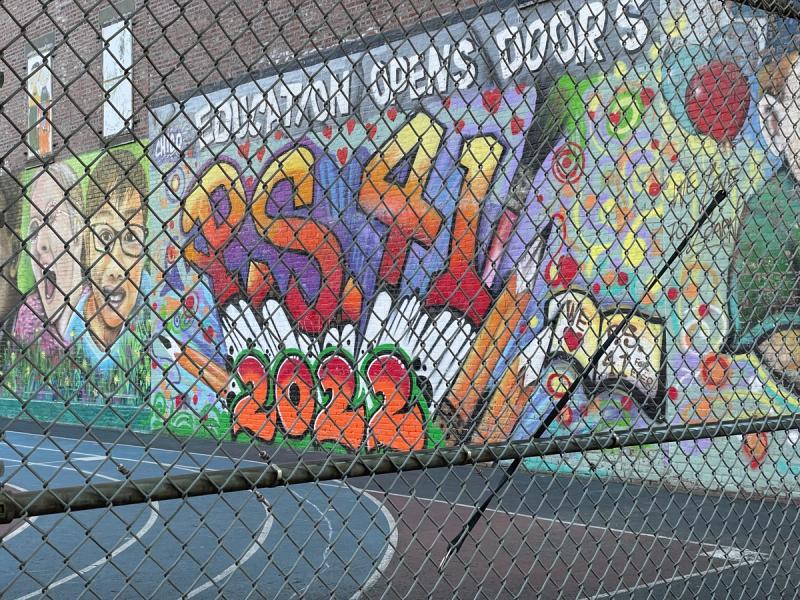

P.S. 41 PLAYGROUND (AT GREENWICH AVENUE AND CHARLES STREET)

Kimmelman: When I was little, P.S. 41 was a progressive school. It was the Village school for Village kids—still is, I’m sure.

One of the things that was characteristic of when I was growing up is that, even when you were little, as an elementary school student, we would go out for lunch. It’s a crazy thought. Nowadays, parents—and I’m one of them—would never imagine sending your fourth-grader out for lunch. But we did that, even though the Village was a lot less safe than it is now, notwithstanding alarmist headlines about crime.

So kids would come and go at the beginning of the day and at lunch, and at the end of the day. By the time I was in fourth grade, I was one of the street monitors. We were kids who had a sash and a badge, and we would stand on the corners to make sure the kids were crossing the street properly. Crazy. But it tells you something about the peculiar nature of the Village.

[Points to the P.S. 41 playground, behind a chain-link fence] This was our playground. This field here is where I shared the trophy as best fifth-grade softball team. It was one of the great triumphs of my life.

So I was a street monitor, and one day, I was late coming back from lunch, because I decided to try a new French restaurant just around the corner there, on Christopher [Street]. I don’t remember what the name of it was—Chez something. And I was late. Who knows, in fourth grade, how long a French restaurant lunch takes. I’m sure it was, in retrospect, like going to Le Pain Quotidien, at the most, probably not even. But to me, it seemed like it was a fancy restaurant, I guess.

I came back late, and my classmate—whose name I could give you, because I remember to this day, but won’t, just in case he reads this—fired me. I was just so upset. I reported to the head of the street monitors, who was a P.S. 41 teacher named Mr. Capiaggi. I remember tearfully going to Mr. Capiaggi and explaining to him that I was really sorry. But I had gone to Chez Marseille around the corner and ordered a quiche, and it took a long time. Something about his reaction, I now realize, was the reaction of an adult public-school teacher hearing one of his students complain that he had gone to a French restaurant—

Bailey: To have a quiche!

Kimmelman: —as a fourth grader, and was late. We were not a wealthy family. Nonetheless, I said I was deeply sorry, and I would never do it again. But I did this, and he replaced me. I remember going home that night and telling my parents this story. I can still see in their eyes that look of “Oh, my God, our child went to a French restaurant for lunch, and then tells this to the teacher as an excuse!”

Why do I tell you this? Because there was about the Village—and about the city even—at that point a kind of openness. To me, it’s a little bit what progressiveness is about. I think it’s why I’ve always felt the city is an open place. Really, it wasn’t incredibly safe. But it was just a different attitude. It was a trust in children, trust that I knew people in the shops. It gave me a sense of ownership of the city, a sense of comfort that this was a place where I could navigate and find my way. Now, the concept of a 9-year-old, 10-year-old, first of all, going into a restaurant alone, but even just walking the streets, is really hard to imagine.

Bailey: And monitoring their elementary-school classmates as they cross the street.

Kimmelman: It seems impossible and totally lunatic, but it didn’t seem that way to me at the time. It was wonderful. We all survived, somehow, and I think it gave us a sense that being a New Yorker was a special thing. I came to understand that only when I went away to school—

Bailey: And later, to Berlin.

Kimmelman: —and met other people. I began to understand that there’s a sense of pride that comes from, as it were, owning the city.

Bailey: So how does it feel to stand on the corner of Greenwich and Charles today?

Kimmelman: It’s an odd thing. I’ve lived now—with my family, raised our children—in Berlin and now in an entirely different part of the city, and they’re very happy there. And so am I. But I am here all the time. Like a homing pigeon. For reasons that have to do with my family, but also because some part of me is drawn back here regularly. I know what you want me to say is “I haven’t been here in years, and it’s wonderful to be back,” but actually, I was here last night. I’m around here with some regularity. I think that also speaks to the way in which the city can be a neighborhood, really be a place where people feel entirely at home. Even a place like this, which seems so anomalous, the Village.

I just want to say one more thing along those lines, which is that the great privilege of my job is that I’ve been able to discover all of these other places in the city, which I didn’t know before, where people have these same feelings. There are literally hundreds of these places. The city is a constant, shocking discovery. And that’s not an advertisement or just words. It’s truly astonishing how complex and beautiful the city is. This is just one place. It happens to be where I was lucky enough to grow up.