Remembering Daniel Brush and His Immaculate, Otherworldly Objects, Paintings, and Jewelry

The first time I ever set foot in the Manhattan studio of the practically indefinable artist-metalsmith-painter-engineer-philosopher-poet Daniel Brush, who died on Nov. 26, 2022, at age 75, he was looking directly at me through his jewelers loupe, which was firmly fastened around his head, just as I exited off the elevator. I found it quite peculiar, at the time, to not be able to clearly see his face or look him in the eyes, but eventually, as I got to know him better (and once the loupe came off), I understood it to be a pragmatic form of protection. With those magnifying glasses on, he was in his happy place. He felt safe, comfortable, at home. Himself. This close-up view was how he saw things. He looked at the world, and the cosmos at large, in microscopic detail. Daniel intimately understood that the largest truths could be found in the most minuscule of places.

A little over a year later, in the fall of 2018, L’École, School of Jewelry Arts, an organization supported by the French jewelry house Van Cleef & Arpels, held a sort of “residency” at the Academy Mansion on New York’s Upper East Side, and as part of it I had the opportunity to join Daniel on stage for a live talk alongside the craft scholar and historian Glenn Adamson and Van Cleef & Arpels’s CEO and president, Nicolas Bos. As Brett Littman, the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in Long Island City, New York, notes here below, public appearances didn’t exactly come naturally to the introverted, monkish, hermetic Daniel. But for some reason, I seemed to have gained his trust, and we had an extraordinary conversation that night.

For the talk, I had asked each speaker to bring along objects for us to look at together in detail. Glenn cheekily pulled out a New York City “Anthora” Greek coffee cup and a dollar bill, Nicolas showed some exquisite archival pieces from the maison, and in a true mic-drop moment, Daniel opened up a box holding a curved, hand-carved, blade-like steel sculpture that he had been working on for, if I remember correctly, at least a decade. The blade had never left his studio, and he had never shown it before publicly or to anyone other than his wife, muse, and 53-year-long partner in their lives’ work, Olivia. By that point in my career, I had already conducted and moderated some 50 or 60 live talks, yet I had never been at a loss for words or questions. That sword silenced me and everyone else in the room. A hush fell over us. The beauty, the wonder, the spine-tingling awe of it—I was nearly brought to tears.

In 2019, I got to spend time with Daniel on two more memorable occasions. The first was for a recording of our Time Sensitive podcast. During the interview, Daniel described exactly the phenomenon I had felt when glancing at his ethereal blade. Making a dramatic gasping sound, he told me, “You know that noise? I love that noise. It’s like this breathless, full, emotional noise. In Yiddish, there’s this word verklempt. It translates to: there’s so much emotion you’re choking because you can’t speak.” After the episode was released, Olivia wrote to me via email, “Daniel and I are verklempt!” That’s exactly how I felt—and still feel—having had Daniel be a profound part of my life over the past five years: verklempt.

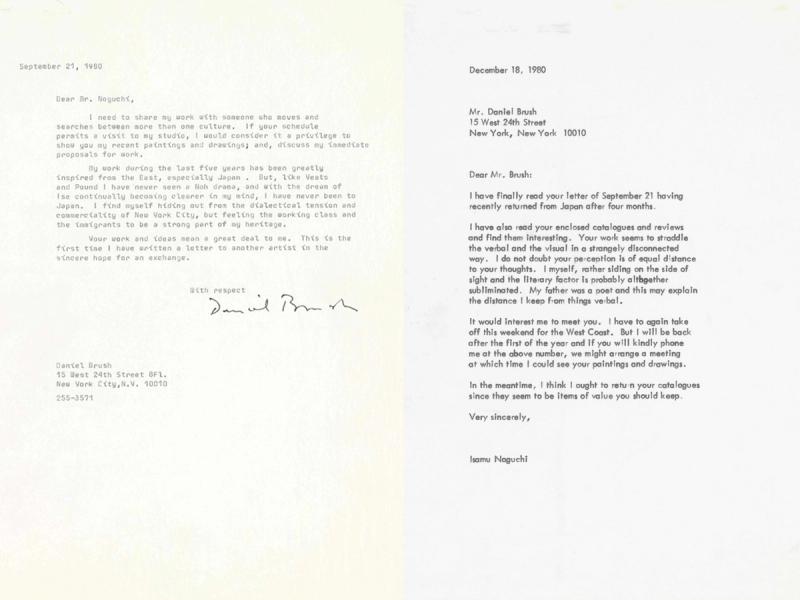

Later that year, I once again returned to the stage with Daniel (and Nicolas, too, although without Glenn this time). We were at the Noguchi Museum, a place Daniel viewed with an almost-sacred level of reverence. Prior to the conversation, Brett had shared with me a letter, found in the museum’s archive, that a young Daniel had written to Isamu Noguchi on Sept. 21, 1980. Much to Daniel’s surprise and delight, I decided to open the talk by reading the letter aloud to him. “Dear Mr. Noguchi,” Daniel wrote, “I need to share my work with someone who moves and searches between more than one culture. If your schedule permits a visit to my studio, I would consider it a privilege to show you my recent paintings and drawings, and discuss my immediate proposals for work. My work during the last five years has been greatly inspired from the East, especially Japan. But, like Yeats and Pound, I have never seen a Noh drama, and with the dream of Ise continually becoming clearer in my mind, I have never been to Japan. I find myself hiding out from the dialectical tension and commerciality of New York City, but feeling the working class and the immigrants to be a strong part of my heritage. Your work and ideas mean a great deal to me. This is the first time I have written a letter to another artist in the sincere hope for an exchange. With respect, Daniel Brush.” Upon hearing his letter, Daniel absolutely lit up and, with a loud cackle, jumped right into conversation.

Noguchi personally replied to Daniel a few months later, on Dec. 18, 1980, writing, “It would interest me to meet you. I have to again take off this weekend for the West Coast. But I will be back after the first of the year, and if you will kindly phone me at the above number, we might arrange a meeting, at which time I could see your paintings and drawings.” Though Daniel and Noguchi never met in the end, it pleases me to think that, in this next life, the two giants are conversing mightily.

In true full-circle kismet, on Nov. 17, 2022—just a week before his death—Daniel was awarded the Noguchi Award. When the museum reached out to Daniel and Olivia about the honor earlier in the fall, Olivia shared that Daniel was in poor health, a situation that unfortunately deteriorated further in the coming weeks. But even from the hospital bed, Daniel was thrilled to accept the award, and during the ceremony, his son, Silla, graciously received it on his behalf. As part of the event, the museum showed a video about Daniel and his work, in which I speak about his endless quest and longing for what he referred to as an “ethereal delicacy.” I’ve been told Daniel was able to watch this video in his final days. I never got the chance to say goodbye to him formally, but it’s incredibly heartening to know that he was able to hear my words of gratitude, appreciation, and respect before he parted from this earth.

Below are three more homages from friends of Daniel’s—Brett Littman, director of the Noguchi Museum; Beth Carver Wees, curator emerita of the American Wing at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Helaine Posner, the chief curator emerita of the Neuberger Museum of Art at SUNY Purchase—as told to me in preparation for the tribute events I helped organize over the past week at the Met and the Morgan Library & Museum.

Brett Littman

Director, Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

“What I appreciate about Daniel is that he seemed to be so out of time. He was someone you might have met in the seventeenth or eighteenth century, yet his thinking was quite modern and contemporary. The other thing is that he was incredibly serious. But then he could be really playful, too. I loved his laugh. When he laughed, it was totally infectious. If you got him to smile and laugh, it was a very special experience.

I met Daniel by chance. In 2007, he had this exhibition at the Phillips de Pury & Company. My friend Gina [Amorelli] was involved in doing graphic design for Phillips, and she told me about Daniel and said he makes these incredible drawings. He was kind of unknown in the art world then and better-known in the jewelry world.

It took a little while for us to get a meeting on the calendar. To be frank, I thought I’d spend about ten or fifteen minutes with him. I didn’t really know Daniel’s oeuvre. So I went there, and we started a conversation. Around four hours later, I left Phillips. It was quite engaging. We really hit it off. I appreciated his way of thinking about the medium of drawing.

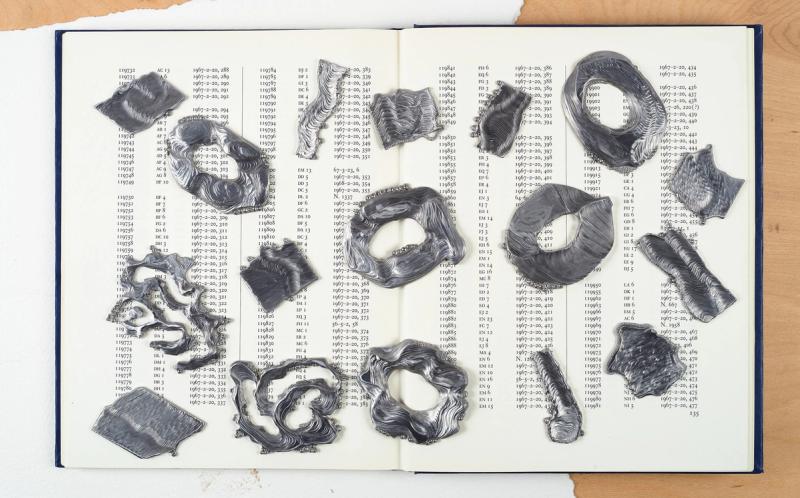

Pretty soon after that, I scheduled a studio visit, just for my own edification, because now I wanted to better understand what he was up to. That was the beginning of visits to Daniel’s studio every year or two, until 2012, when I got a call from David [Revere] McFadden, who was organizing a large show of his work at the Museum of Arts and Design [MAD]. David asked me if I would write a catalog essay about Daniel’s drawings. So that was a more intense period. We looked at a lot of his drawings, talked a lot about the idea of line in his work. He also engraved and beveled and drew lines in all kinds of metalwork, even in some of his jewelry.

I published that essay in the Steidl book that MAD produced, which may be the most beautiful book I’ve ever been featured in, because it includes hundreds of pages with metallic ink. When you look at the pictures of his work, they glow on the page. Oliver Sacks had written something for it, as well. It was really an incredible experience.

There’s one other anecdote that I want to add: Daniel was not an enthusiastic public speaker. He really did not like talking in public at all. And David was having a hell of a time getting him to agree to do anything at MAD in the public realm. I guess Daniel said, ‘Well, I like talking to Brett. Maybe you can ask him to be part of the tour?’ So I got roped into doing the tour with David and Daniel—the only tour I think he did for the whole show at MAD. It was a wonderful, totally manic, crazy experience. People were so enthusiastic to hear Daniel talk about the work and to engage with him. After that, he maybe became slightly more comfortable with public speaking. I feel like, in my small, little way, I helped him, in that particular situation, to get out there in the world.”

Beth Carver Wees

Curator emerita, the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

“One of the reasons I was so attracted to Daniel, besides his work, is when we first started talking, I realized that he and I think about jewelry in a similar way: It’s not just about adornment—beauty, sure. He understood the history of jewelry and how it was all made.

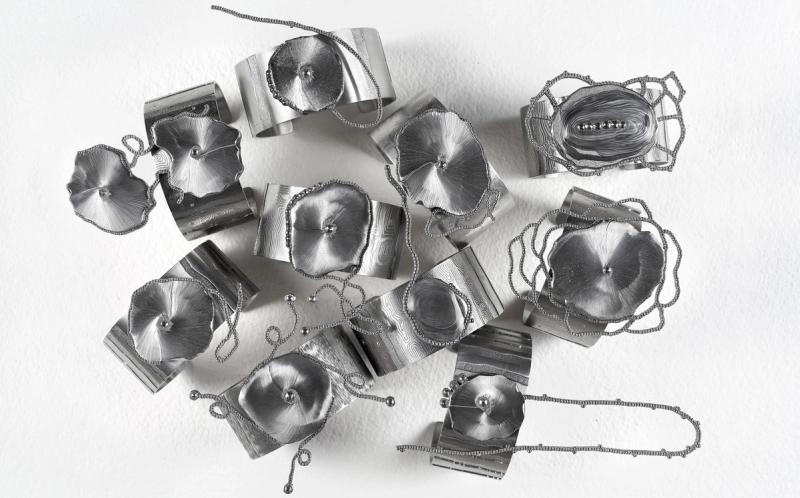

To me, one of the great pleasures of studying any art, but particularly jewelry, is that it doesn’t really matter where or when it’s from. It could be devotional, talismanic, protective… When we were working on [the 2018 exhibition] ‘Jewelry: The Body Transformed,’ he and Olivia gave [his piece] ‘Torque’ to the Met. There were six curators planning the exhibition, all from different departments, and we had to use objects in the Met’s collection. So I just asked, ‘Is there any chance you might be able to donate a piece?’ And Daniel and Olivia, being the generous folks they are, donated ‘Torque.’ What I like about ‘Torque’ is that it’s an ancient form that he completely revolutionized. He bought this boring, gray aluminum tubing for airplane refrigeration coils, engraved it to its death, and then studded it with diamonds—some new, some Mughal. We ended up installing it as the very final object in the exhibition. The exhibition started with Egyptian gold sandals, and we ended it with Daniel’s ‘Torque.’

With Daniel, his work was always a quest. He would achieve something like putting seventy thousand granules on a dome shape and not be happy with it. He always thought it could be better, which is maybe what made him unique. Most people would say, ‘It’s done.’ But not Daniel. He kept searching.

One other thing: My background is in antique silver, both British and American. I came to jewelry through that a long time ago. The piece at the Victoria & Albert Museum that Daniel often talked about seeing as a 13-year-old, this Etruscan gold bowl [dating to 650-700 B.C.], really speaks to me. I mean, the idea of a 13-year-old falling in love with something that’s not a dinosaur or a piece of armor! It was just a tiny gold drinking bowl!”

Helaine Posner

Chief curator emerita, Neuberger Museum of Art, SUNY Purchase

“I met Daniel as an art history student of his at Georgetown in 1975. I had studied art history, mostly historic stuff, especially during that period of time. There were almost no contemporary art courses available at Georgetown then, and it was the first time I took a studio art course, which I needed to do as part of my art history degree.

There was Daniel, a complete anomaly at Georgetown, which can be a very formal and buttoned-up place. He was blazingly intelligent, enormously articulate, totally passionate, just an inspirational figure. This was wonderful to me. There were opportunities for one-to-one conversation; we had our painting assignments, which frankly, I don’t remember at this point; and then he would walk around the classroom and speak to the students about what they were working on. There was a kind of dialogue that one didn’t get very often. He would also sit down and teach us more formally about what was happening in the contemporary art world, including color field painting and abstraction. And he’d talk about his own body of work—the influence of the Noh theater, his meditative focus. It was something that I would describe as very pure. Olivia used the word ‘uncompromising’ to describe him when she and I recently spoke. I think she said ‘eccentric and uncompromising.’ And I thought, Boy, does that get it! It really is true.

I feel like Daniel taught me about art, and about one’s dedication to one’s field. About a kind of single-mindedness, and a set of values that I’ve carried through with me through the rest of my career. I’m a curator, and have been for some time, and I’ve always put the artist at the center of my work. Always. I’ve tried to be true to their vision, whether it’s a one-person show or group show. I think that’s something I learned from him. That you value these relationships and be respectful. You understand their contribution to the culture, which is greater than the curator’s contribution. This has kept me inspired and humble. It has given me a life that hasn’t let me down. When I graduated, Daniel gave me a small painting called ‘Voices,’ and it sits right across from my desk to this day. He’s always kind of whispering in my ear.

About ten years after I graduated from Georgetown [in 1986], I was curator at the University Museum [of Contemporary Art] at the University of Massachusetts. I was able to do a show of his drawings, “Cantos for an Accompanying Role.” It was really wonderful, for me, for it to come to that moment. He will always be my teacher—always—but I was able to be his curator for a moment there. We did a beautiful show.”